|

Vol. VI, No. 1, Summer 1992 / No. 2, Fall 1992 |

Landscape

The Ozarks of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

A Land that Used to Be

By J. Kenneth McCarty

Ken McCarty is a natural resource manager for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. He is involved with a number of prairie, savanna, forest, and wetland restoration projects throughout Missouri's State Park system.

I have often dreamed about what the Ozarks that I now know must once have been like. Perhaps you, too, have gazed across the Ozarks scenery, wondering what used to be there. What did the Indians see where those houses and highways are now? Would those fescue pastures have been forests? What filled those bottomland fields? What were the woods like then? Where did the elk and bison roam? How much clearer were the streams?

Picture for yourself the east-central Missouri Ozarks, from Potosi not quite to Salem -- the country of the Courtois, Huzzah, and upper Meramec Rivers. Think of it as it looks now. Imagine next the rolling Salem plains; visit the Current; jog west across the North Fork to Table Rock Lake country; then north to the farmlands south of Springfield. Now swing your mind back to earlier times, and see through the writings of explorer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft what this part of the Missouri Ozarks looked like 173 autumns ago.

Darkness fell Thursday, November 5, 1818, around an abandoned Osage Indian wigwam built of poles and bark, on the banks of Bates Creek just west of Potosi in east-central Missouri. Inside, fuelight flickered on the pole framework and lit the faces of two young men. They had discovered this lodge on the first day of a cross-country adventure into the interior Ozarks.

It sat near the edge of the enormous Ozark wilderness, through which their wanderings the next three months would take them -- often quite lost -- away from the normal highland travel routes and into its most remote interiors. Their trip came at a moment when the Ozarks passed from a land shaped and used by the native peoples for several thousand years, to that of the American settler. Treaties would soon push the already displaced Native Americans from the East, then living in the eastern Ozarks, still further west. Backwoods hunters repeatedly cautioned the explorers that the area they were about to enter was still the regular summer hunting grounds of the powerful Osage. It was a wild landscape, and this first evening of the trip, they -- like we -- could only imagine what things they would see.

As darkness closed around the traveller's camp they put fresh wood on the fire, "which threw a rich flash of light on the Indian frame-work of our camp, and amidst ruminations on the peculiarities of our position, our hopes, and our dangers, we sank to sleep."

When Schoolcraft and his companion Levi Pettibone led their horse Butcher away from the Osage wigwam, they (in Schoolcraft's words) traveled across a succession of elevated and arid ridges called the Pinery, where sterile, hard, and flinty soil bore yellow pines with some oaks and scanty vegetation. Later, Henry remarked of this eastern pine belt that the hills also yieM sassafras, and the slopes which are richer soil also afford buckeye, black walnut, papaw, and percimmon [sic], and some other trees, shrubs, and wiM fruits; and the whole is covered in summer by a luxuriant growth of grass, even the poorest hills, which hide the flinty aspect of the country [remember, they were travelling during the winter] and gives it a very pleasing and picturesque appearance.

Their path was leading them along the Osage Trace to the Courtois River. "Not a habitation of any kind, nor the vestiges of one, was passed; neither did we observe any animal, or even a bird." The Courtois Valley did possess some rich lands, but they did not extend far and soon the men reentered a succession of sterile ridges, thinly covered with oaks that led them to an eminence overlooking the Huzzah. "This valley consisted entirely of prairie. Scarcely a tree was visible in it." Schoolcraft noted that the river had extensive prairies all along its banks. "On leaving the valley of Osage Fork [the Huzzah] we immediately entered on a hilly barren tract, covered with high grass, and here and there clumps of oak trees." They traveled that day over barrens and prairies, with occasional forests of oak, the soil poor and covered with grass, with very little underbrush.

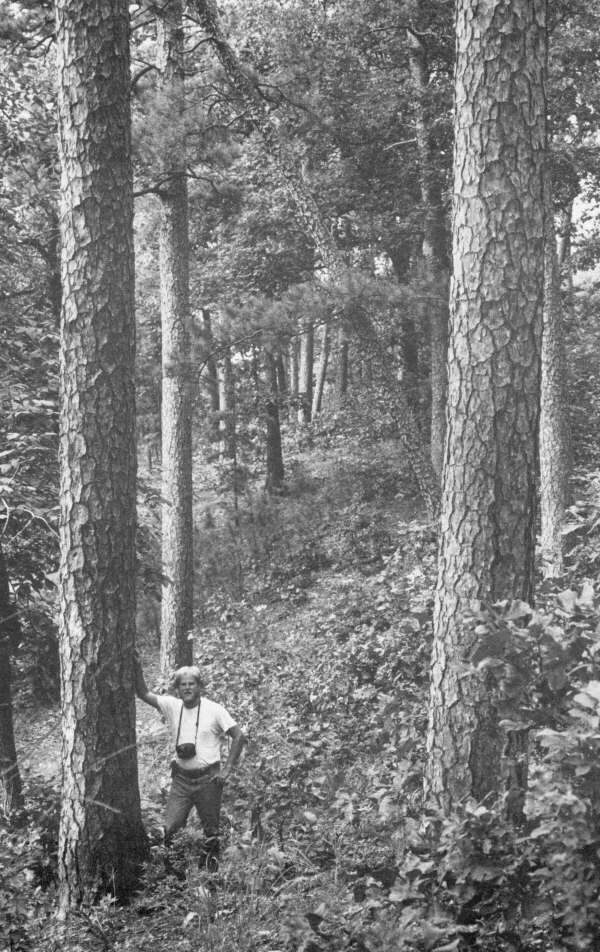

Perhaps the lack of typical forest here is surprising. In fact, the prairies and savannas Henry describes ("barrens'' in his 19th century terminology) were once common throughout the Ozarks. In his narrative they are the most frequently encountered landscape across the Ozarks uplands. Along this particular leg of his route, the savannas were very open and orchard-like because of the frequent fires that Indians set to preserve them for their wildlife resources. Where today we see tightly packed forests and fescue pastures across the regions of the Salem-Potosi Ranger District of the Mark Twain National Forest, and Indian Ridge State Forest, imagine instead bison and elk grazing among scattered oaks, their wide horizontal branches arching over grasses tall enough sometimes to hide people on horses. Hundreds of species of wildflowers decorated the landscape.

[30]

As they came near the sources of the Meramec river, Schoolcraft wrote,

we entered a wide prairie, perfectly covered for miles with these leaves, brought from the neighboring forests. At every step the light masses were kicked or brushed away before us. This plain, or vale, was crowned in the distance by elevations pinged with tall trees, which still held some of their leafy honours, giving a very picturesque character to the landscape .... We were in a region teeming with the deer and elk, which frequently bounded across our path.

They entered the valley of the"Merrimack" as evening approached, and camped in a prairie near its source. He noted that "some good bottom lands are found on its banks, but the adjoining hills are stoney and barren, covered with little timber and high grass."

***

Who today, picturing the thickly wooded valley of the Meramec, would think of it once in prairie, overlooked by hillsides rich in grass with only a scattering of trees ?

The next day, Henry and Levi left the Indian trail, and "struck through the woods on a south course" east of the rolling uplands that would one day be the site of Salem, Dent County. They camped on the bank of a small lake, in a prairie containing several small ponds or lakes, having traveled twenty miles through country they described tersely as "Lands poor; trees, oak; game observed, deer and elk." Henry complained that "One of the greatest inconveniences we experience in travelling in this region, arises from the difficulty of finding, at the proper time, a place of encampment affording wood and water." Wolves howled through the darkness around their campfire that night.

[31]

[32]

They continued their journey another eight miles across "the prairie of Little Lakes .... a barren prairie country with little wood and no water," that took them past the uppermost end of the West Fork of the Black River, "into the lofty forests of pine" and "through valleys and deep defiles of rocks for several miles" to the banks of the Current River.

Their route crossed present southern Dent and northern Shannon counties from east of Salem to the Current river just south of Montauk State Park. The rolling uplands Schoolcraft described are still open today--but clothed in domestic pasture rather than wild meadow. Large expanses of the more rugged hill country leading down to the Current remain forested, but these contemporary forests are more densely shaded and less packed with wild grasses and flowers than were the fire-influenced ones that Schoolcraft saw. Still, the forested valley of the Current River is superficially the least changed of any modern area along Schoolcraft's route.

Henry called the Current "a fine stream, with fertile banks and clear sparkling waters." It sat in "a deep romantic valley...covered with a heavy growth of trees--a dense forest of hard wood, with every indication of animal life." The water, he said, was "very clear and pure. The surrounding country afforded some of the most picturesque and sublime views of rural scenery which I have ever beheld."

Leaving the Current River valley proved difficult. The hills were too steep to climb so they traveled up the valley several miles until brush and brambles became so thick they had difficulty in proceeding. They turned west through several steep valleys of "sere" vegetation. It was rough going over hilly ground and shallow soil covered thinly with yellow pine and shrubby oaks. Many places had such thick brush that the horse "could not be forced through."

When they reached an area in present Texas County southeast of Houston, they found prairies and savannas where today we see fields and forests. "The first view of this vista of highland plains was magnificent," wrote Schoolcraft. "It was covered with sere grass and dry seed-pods, which rustled as we passed. There was scarcely an object deserving the name of a tree." It was "a dry and wave-like, high-land prairie ....generally level, and with very little wood or shrubbery ....a level woodless barren covered with wild grass, and resembling the natural meadows or prairies of the western country in appearance." Only an occasional oak was encountered; sometimes a cluster of bushes crowned the summit of a sloping hill. Wandering past "bleached bones of the elk, deer, and bison," Schoolcraft wondered if this were not the region where DeSoto's messengers first encountered the buffalo.

Continuing south and west of Houston, they crossed the uppermost reaches and tributaries of the Big Piney. These streams were noteworthy to the travelers for being thickly interwoven with brush while the intervening ridges were "little else but a pile of angular stones, with here and there an oak tree set upon it." The savannas continued south across the elevated ranges of hills "covered with large oaks bearing acorns," in which they chased groups of bears that were soon lost because "the tall grass screened them from our sight." These oak-covered barrens covered the entire succession of ridges that led to what Schoolcraft called "a very great elevation" on the watershed divide just west of modem Cabool, in Texas County. Along it, Henry marveled at the large numbers of elk and bear they encountered.

Descending southward from this divide, Schoolcraft gives us a picture of what western Ozark floodplains were like. The North Fork River, in extreme northeast Douglas County, began as clumps of bushes, with gravelly areas between, and an occasional standingpool of "pure water" on the prairie. It grew, he wrote, in "plateaux or steps, on each of which the stream deploys in a kind of lake, or elongated basin, connected.., by a rapid." It was fed by springs "which gush at almost every step from its calcareous banks." Soon it became a major river, possessing some fertile, heavily-timbered bottoms. The soil was "that rich alluvion which is common to all the streams and rallies of Missouri." The timber included elm, oak, beech, maple, ash, and sycamore. It was not open timber, but had "shrubs, vines, cane, and green-briar.., the latter of which often binds masses of the fields of cane together, and makes it next to impossible to force a horse through."

Of the water itself, Schoolcraft observed that its "purity and transparency are so remarkable, that it is often difficult to estimate its depth." Beyond, the cliffs sometimes rose to astonishing heights, and were uniformly crowned by the yellow pine. Behind the bluffs on the west lay more open prairie, "illimitable fields of grass, with clumps of trees here and there." They traversed these prairies for awhile, and found that "traveling was free, unimpeded by vines [or] shrubbery .... We sometimes disturbed covies of prairie birds; the rabbit started from his shelter, or the deer enlivened the prospect."

Returning to the river, they found its character to change as rich bottoms were replaced by high oak prairies west of present day West Plains. The perpendicular bluffs and the pine also disappeared, and in their place were long sloping hills, covered by oaks. Once again it is savanna-- not forests as we might expect--that Henry sees, and it causes him to remark that the timber on those eastern slopes of the North Fork was so open that they could not get near any large game.

[33]

Soon they struck out across the uplands to the west of the North Fork's southern reaches, through still more open oak forest. Past "trees, rocks, prairie-grass, the jumping squirrel, the whirring quail, over elevated ridges of oak-openings, we gave them a glance and passed on." Their food supply was gone, reducing them to eating acorns and woodpeckers, and chewing branches of sassafras, "which took away the astringent and bad taste of the acorns."

Schoolcraft and Pettibone were trying to reach the scattering of settler's cabins along the White River of southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas. Worn down as they were by rain, fatigue, and lack of supplies, their view of this rugged country north of present day Bull Shoals Lake was depressing. "Hill on hill rose before us, with little timber, it is tree, to impede us, but implying a continual necessity of crossing steeps and depressions." Stream valleys were filled with brush and small canes, but open enough that grass re-greened from a fall fac was able to recruit Butcher.

Several more difficult ascents through rugged hills west of the Little North Fork brought them out on an extensive prairie of varied surface. Climbing "a bold, mound-like hill" they looked out upon prairies and groves in an "undulating vista" as far as the eye could see.

Little wonder that bison were among the wildlife hunted by the settlers he would soon meet, or that this is cattle country today.

Travel through the more dissected, southern reaches near the White River was through lightly timbered, hilly country. Beyond Beaver Creek, the country they saw was completely denuded of trees and shrubbery.

[34]

Beaver Creek itself proved to be a "beautiful, clear stream of sixty yards wide, with a depth of two feet, and a hard, gravelly bottom." Like the North Fork, it was covered by a heavy forest of oak, ash, maple, walnut, mulberry, and sycamore, with a vigorous understory of cane. From its banks rose 300 foot perpendicular bluffs, capped by a stinted growth of cedars and pine.

Crossing Beaver Creek, Henry, Levi, and two locally recruited guides turned northwest into an entirely different type of terrain. What we now call the White River Glades Region presented to them a character of unvaried sterility, consisting of a succession of limestone ridges, skirted with a feeble growth of oaks, with no depth of soil, often bare rocks upon the surface, and covered with course wild grass; and sometimes we crossed patches of ground of considerable extent, without trees or brush of any kind and resembling the Illinois prairies in appearance, but lacking their fertility and extent. Frequently these prairies occupied the tops of conical hills, or extended ridges, while the intervening valleys were covered with oaks, giving the face of the country a very novel aspect, and resembling, when viewed in perspective, enormous sand-hills promiscuously piled up by the winds.

Henry was crossing the lands in and around the Ava Ranger District of the Mark Twain National Forest, including the present day Hercules Glades Wilderness Area. Vast tracts with this same wild mountainous flavor still occur there, although where Schoolcraft's rocky hillside prairies used to exist, today will be found amore closed,forested landscape interrupted by large bands of cedar thickets, (What Schoolcraft called "hillside prairies" we now call glades--shallow-soil grass and wildflower meadows surrounded by forest). Elsewhere, most of these rugged prairie-like hillsides have become fescue pasture, or brushy forests of oak and cedar.

They reached and ascended Swan Creek valley, then a rich alluvial bottom covered with a heavy growth of maple, hickory, ash, hackberry, elm, and sycamore. To its northwest lay an "elevated plain or prairie, covered, as usual, with ripe grass." Passing Findlay's fork and proceeding to the James River (just southeast of present day Springfield), Henry described a gently-sloping surface of hill and dale, partly covered with forest trees, and partly prairie. "I have seldom seen a more beautiful aspect," he wrote.

In exploring the valley of the James, Schoolcraft discovered that "along the margin of the fiver, and to a width of from one to two miles each way, is found a vigorous growth of forest-trees, some of which attain an almost incredible size." The river banks were skirted with cane, to the exclusion of other underbrush. Away from the bottoms the lands rose gently for a mile or so, terminating in highlands without bluffs, possessing handsome growths of hickory and oak. "Little prairies of a mile or two in extent are sometimes seen in the midst of a heavy forest, resembling some old cultivated field, which has been suffered to mn to grass."

Schoolcraft was enthusiastic about the prairies that began just west of the James River. They are, he said, the most extensive, rich, and beautiful, of any which I have ever seen west of the Mississippi river. They are covered by a coarse wild grass, which attains so great a height that it completely hides a man on horseback in riding through it. The deer and elk abound in this quarter, and the buffalo is occasionally seen in droves upon the prairie, and in the open high-land woods.

Here he is extolling the wonders of tall grass prairie, which once covered one third of Missouri. The very tall grasses referenced were primarily big bluestem and Indian grass, which in some circumstances will grow ten feet tall. These are but two of the several hundred plant species that grew on Ozark prairies. Summertime floral shows were often spectacular, and drew frequent comment from early travelers. Bison, deer, and elk loved the prairie grasses and several of our now endangered wildlife species required them. The prairies that Schoolcraft describes here are mostly farm and domestic pasture land today.

They camped several days to explore this country that Schoolcraft found so enticing. He described it as a mixture of forest and plain, of hills and long sloping valleys, where the tall oak forms a striking contrast with the rich foliage of the evergreen cane, or the waving field of prairie grass. It is an assemblage of beautiful groves, and level prairies, of river alluvion, and highland precipice, diversified by the devious course of the river, and the distant promontory, forming a scene so novel, yet so harmonious, as to strike the beholder with admiration.

And then, after this pleasant camp upon the prairie of the Springfield plateau, Schoolcraft and Pettibone began their long return trip to the east--down the White River into Arkansas Territory, then north again to Pososi, where they arrived on February 4.

Change --both natural and cultural -- has been going on for so long that we record it in eras. Schoolcraft and others, however, have told us what our Ozarks once was like. As a boy, I dreamed of it as a vast unbroken "forest primeval", but I now know that the first Ozarks was a rich and varied collage of prairies, savannas, glades, and both more and less open woodlands; all intersected by networks of dense floodplain forests that were themselves quite variable. This diversity of landscapes and ecosystems was one of the keys to the area's former abundance of plant and animal life. Compared to today, much seems changed-- yet there is still much to hold on to.

[35]

In some places, efforts of various individuals and organizations are keeping portions of the native Ozarks alive. The United States Forest Service has restored and is preserving large expanses of the colorful and diverse glade region that Henry Schoolcraft and Levi Pettibone crossed. You may explore it along the Gladetop Trail southwest of Ava, or find similar landscapes that are being actively managed or restored at Ruth and Paul Henning State Forest near Branson, or on Long Bald Natural Area at Caney Mountain Wildlife Management Area in Ozark County, the latter are efforts of the Missouri Department of Conservation. Prairies and "barrens" (now called savannas) are nearly extinct --especially along the explorer's route; but excellent examples may be sampled at Prairie State Park near Liberal (for prairies), and Ha Ha Tonka State Park near Camdenton (for savannas). Both are preservation efforts of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. The Nature Conservancy' s Victoria Glade near Hillsboro preserves a colorful and diverse piece of the stony eastern Ozark glade country; a relict virgin pine stand can be seen along Highway 19 near Round Spring; and a variety of other restoration projects large and small, public and private, are happening across the Ozarks today.

Much of the Ozarks which Schoolcraft saw is indeed a land that used to be. But many beautiful features remain. With strong restoration and preservation efforts, and with good stewardship, our Ozarks landscape will long continue, using Schoolcraft' s words, "to strike the beholder with admiration.

[36]

Map of Schoolcraft's Route. This map of Schoolcraft's route was prepared by Dr. Milton Rafferty, Head of the Department of Geography, Geology, and Planning at Southwest Missouri State University. It will be included in A Joumal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansas in 1818 and 1819, soon to be reprinted by the Univeristy of Oklahoma Press. Dr. Rafferty is preparing an introductory chapter and additional maps for this book.

Nov 6 Left Potsi.Nov 8 Last inhabited cabin they would encounter until White River.

Nov 8 Passed village of Delaware Indians.

Nov 12 Spent two days at Col. Ashley's saitpetre cave.

Nov 17 Decided they have deviated too far north--

alter course from SW to SSW. Nov 19 Pettibone sprains ankle while chasing four bears.

Nov 19 Horse took a bad fall down ridge.

Nov 20 Noted large spring at river.

Nov 21 Baggage almost totally ruined while crossing river.

Nov 22 Came upon large cave. Carved date in rock.

Nov 25 Spent night at deserted White Hunter's camp.

Nov 27 Provisions exhausted. Set out without horse to find cabin.

Nov 28 Ate acorns for supper.

Nov 30 Found horsepath that led to Well's cabin on Bennet's Bayou.

I Departed Well's cabin to go back to camp for horse and baggage.

Dee 6 Horse almost sank in swamp.

7 Spent night at M'Garey's.

9 Arrived at Sugar Loaf Prairie.

12 Arrived at Beaver Creek cabins.

Bite 25 Killed 14 turkeys for Christmas dinner.

Dec 28 Set out towards north.

Bee 31 Killed one deer, two turkeys, one wolf, and one goose.

Jan I Stopped to explore cave.

Jan I Set up camp near deserted Indian mines.

Jan 5 Feasted on honey from bee tree.

Jan 9 Stopped to explore cave.

Jan 12 Setup camp near deserted Indian mines.

Jan 14 Lent canoe to trader.

Took horsepath to Matney's on Great North Fork.

Jan 17 Set out again in canoe.

Jan 17 Passed Crooked Creek.

Jan 17 Stopped to examine Cailco Rock. Jan 17 Spent night at widow Lafferty's. Jan 19 Set out on foot from Poke Bayou.

Jan 19 Schoolcraft sprains ankle--slows progress.

Jan 20 Pettibone went on ahead while Schoolcraft reste. Jan 22 Stopped at Dogwood Spring, a noted resting place. Jan 23 Crossed Spring River by canoe.

Jan 24 Crossed Eleven Point River by canoe. Jan 25 Crossed Current River at Hick's Ferry. Jan 27 Ferried over Black River in canoe. Jan 28 Crossed St. Francis River at village. Jan 30 Headed towards Belleview.

Jan 30 Noted country becoming rough and barren--blocks of granite. Feb 1 St. Francis River was too flooded to cross so headed to St. Michaels.

Feb 2 Passed through St. Michaels.

Feb 3 Passed through Murphy's Settlement.

Feb 4 Arrived in Potosi.

The map was machine drafted by Joan Betz, staff cartographer of the Department.

Photo Credits: Department of Natural Resource, photos by Paul Nelson.

[37]

Copyright -- OzarksWatch

Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues | Keyword Search