Volume 2, Number 12 - Summer/Fall 1967

Life in the Ozarks - Then and Now

by Margaret Gerten Hoten

(Continued from the Spring of 1967 Quarterly)

Another winter came and a New Year again. We planned ahead what crops would be best for winter food, and planted our fields and garden when the weather was warmer. It was a good spring, fruit trees and bushes were loaded with blossoms, and in time with fruit. There were lots of cherries for pies and to can, and every bush and vine covered with juicy berries. We managed to get enough jars to put up what we did not use fresh, and the peach and grape crop would be ready later on. Every growing thing did well in the Ozarks if given a little care. Minerals in the ground probably accounted for this. The fruit and vegetables had a tine flavor and color, though not as large as those grown in California or in some other sections. Very few trees here were grafted, which accounted for the difference in size. Seeds also were saved from year to year, and seldom ordered from a different locality.

The first grape vines that had been planted, had borne an abundance of fine grapes of several varieties. We could not commence to use them all for jam or jelly, nor could any be shipped, as they would not have stood the long rough trip by wagon to the railroad.

People here would have taken them had we picked and taken them to their doors—as a gift. But we had no time for this. Our German friends had plenty of their own, so we made wine of the surplus. This was the product of 80 vines, Father had 700 younger vines planted on the north slope of our hill. His dream was to gradually plant the 80 acres in grapes, and hope for the railroad to come. He was corn n the Mosel Valley in Germany, and often said he had never seen climate and soil as suited for growing grapes as I was here in the Ozarks. He had great hopes and dreams.

Our hill-top corn field did better than expected, the question was; how to bring the crop down the hill to the barn. It was too steep for a wagon, and jeeps had not been thought of yet, so again necessity brought the answer. Father made a sledge; the runners were heavy oak, with strips of iron from old wagon tires attached to the bottoms. We would load this contraption with fodder or corn, then start down. We held the sledge back with ropes when it got to the steep part of the trail, to keep it from running the horse down, he moved as fast as he could, but we took no chances. Later on the sledge came in handy hauling rocks from fields, to where we had started more walls.

This had been our best year so far, we had worked hard to enrich the garden and take care of the orchard and vines, this all meant more food. We felt it repaid us for the extra hours of work. Meat was still the one item that was not plentiful, with pork being the main stand-by. Chickens, what the hawks and varmits did not get, and young squirrels and rabbits which were plentiful, were a welcome change. Quail were numerous; but hard to get. One could ride into a flock of 75 to 100 and they would run between the horses hooves, but try to get within gun shot of them on foot! So we were vegetarians mostly, but did survive.

Late that fall there were wild turkeys reported in the woods not far from home, so Henry took his old muzzle-loading shot gun and went out to try and find them. Along in the afternoon I saw a flock of at least twenty calmly marching through our nearest field. I was all excited, and got close enough to see the long plumes floating out from the gobblers, or "Tom turkeys" breasts. I hoped that Henry would appear before they were gone, but no such luck. They strutted across the field, flew the fence, and disappeared into the woods.

The rains had come in time this summer to insure a good late crop. Our cane was cut and ready for the man who went from place to place with his mill to make it into sorghum molasses. He received a third of it as his share for his work. We had stripped all the blades from the stalks, next topping them, then cut the stalk close to the ground. After stacking the stalks in a huge pile, a trench was made for the fire and a rock oven built to set cans in, that held the Juice. There would be three of these, each one set lower than the other. The car was crushed in a mill, run by horse power, the juice poured into the top pan, the fire was kept burning at a steady heat. By the time the juice reached the third pan it was molasses; having been skimmed while cooking, it was a clear amber color. The man in charge would taste it and say, "Them's good molasses, them suits my taste." I never did find out why molasses was always referred to as them.

"We had a 50-gallon barrel full as our share, also the tops (seed) which made feed for the chickens. The blades, after being well dried, were good feed for any of the stock. Cane was a crop that did well, none of it was wasted. Yet many did not plant it, but paid fifty cents for a gallon bucket of thin syrup at the store. This was a man's daily

[11]

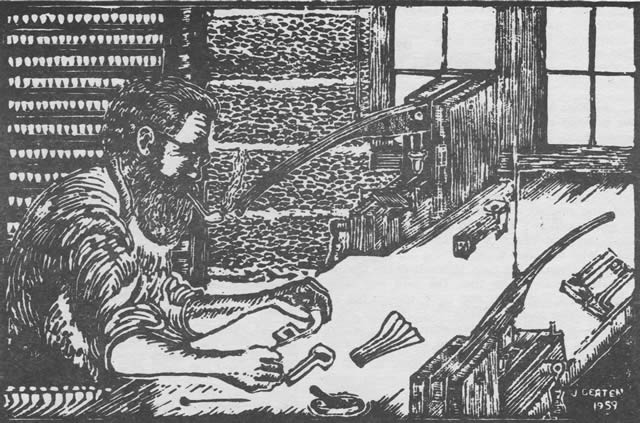

"The Pipemaker" by John Gerten

wage here! Most of the people did not try to save feed for their stock, and only fed the horses a little corn when they worked them.

We had dried many peaches. The beans, cow-peas and our corn, cotton and peanut crop was so much better that we were all encouraged. That fall John and I had taken the job of picking cotton for our neighbor just down the big hollow from home. It was very poor, not more than 18 inches tall, and the boils were small. We were paid 50 cents a hundred pounds. The field was full of cockle burrs, and in two days our coarse stockings were in shreds from pulling burrs off them. We each had a gunny sack tied around the waist with rope, and had started our first day of picking full of vigor, and big plans for the money we expected to earn.

At noon we stopped near the spring to eat our lunch, we were pretty tired, our sacks were only half full. By now the sun was beating down, and as we were in a stooping position all the time, our backs were aching. By the time we had our bags full; we could tell by the sun that it was time to quit for the day. Imagine our disappointment when our sacks were weighed, we had just 100 pounds of cotton between us. We had earned only 50 cents all day! We had heard that some men, when they hauled the cotton to the gin would pour water over it so that it weighed heavier. If the gin owner said it was damp, they would answer that it had set out in a heavy dew all that night. We were too honest to do anything like this!

We picked the field. It took us over a week, and we made about $4.50 all told, it was not much for all the back-breaking work we had done, but we felt proud that we had been able to earn this much. After all calico was only five cents a yard, shirting, which we were using for skirts as it did not catch and tear on brush, was ten cents a yard, so our money went quite a ways at that. Coffee, the package kind, was often two pounds for 25 cents; oil for lantern or lamp, ten cents a gallon; sugar, $5.00 per 100 pound sack. All goods was in a lower price range than it is in these days of higher wages. But the fact that there was no way to earn cash pay for what little work there was, as much was in trade for any thing some one had that you needed. So it was hard sledding the year around. A man working on a farm received $10.00 per month and his room and board. As most families had growing children; there was not even work of this kind.

The boys set traps and caught quite a few skunks that winter. On moonlight nights I often went with them and the two eager dogs to hunt for ‘possum. It was light enough to read news print when the moon was full, and just a few fleecy clouds drifted around. We would climb a hill and it was a beautiful sight, we could see for miles. In the distance we could hear the baying of the hounds, as others were out to get a few hides also, the hides were not good in summer, but late in fall the varmits had new winter coats. The hounds were full of pep; after loafing in the shade all summer. Some men had as many as six or more of these lanky, sad-eyed and lop-eared dogs, whose main purpose in life was to lay around in the shade in summer and near a fire-place in winter.

The Muller family, who were also from near our home in Illinois, had moved down to their claim from a rented place that winter, after Mr. Muller had inherited money from his father’s estate in Germany. They started to build and improve at a steady rate, having done only as much as required by law since filing the claim. Later on another family of German descent, from Nebraska, settled about three miles from us, and we visited with them and the Muller family. Mr. Anton was a carpenter by trade, and before long was building a house in his spare time for a young couple who were running the store. He then had a way of earning some cash when needed. They had children of our age, and we had the first social life since coming to the hills.

Winter as usual, brought increased activity. The more land we cleared, the more space to grow crops we had. There was always grubbing out post-oak and sasafrass sprouts, and rocks that had been plowed up to haul off. We could have enjoyed a little more rest, but we knew by now is was "root hog or die" so we rooted! Several times a week it was my job to ride a big flea-bitten grey to the store and Post Office. Women rode side-saddle, and some times it was a wonder that I made it home at all. I had a sack of groceries on my lap, held a can of kerosene with my left hand, and the reins tight with my right. The trail winding down the hill was steep and rocky, and one had to keep the horse’s head up. The real trick was to hang on to the load and duck branches of trees. Somehow I made it.

After crops were planted that spring, Mr. Muller invited us to go with him and his children to visit a large cave. We had heard about it and were glad to go. It was claimed to be the largest in America, located in the Shepherd of the Hills country near Branson, it is known as Marvel Cave now. As it was some distance by road we took a lunch with us, also lanterns. We got there about noon, and after eating lunch we all set out to explore.

First we ran down a steep slope to a hole about four feet wide. The top of a tall tree trunk was visible in the opening. The stubs of branches some two feet long had been left on the trunk,

[13]

and we had to climb down this natural "Jacob's ladder", stepping on a branch and sliding to the next one.

Now we were just a few yards from the entrance, and the lanterns were lighted so we could see the way. As we entered the cave, bats, disturbed by the lights, flew to dark corners. It was a beautiful sight. Stalactites like giant icicles were everywhere; in the light of the lanterns they glittered like diamonds. We kept on going, sometimes through narrow passages into larger rooms. Once we walked a narrow path around a deep hole, we threw rocks into it, but could not hear them strike bottom. I was sure glad when we got past it. Finally on reaching a place where one would have to lay flat and slide through a low, narrow opening, we all decided we had seen enough, and started back. We made it without any trouble, and on reaching the outside were surprised to see the red glow of the setting sun. We had not realized that we had been in the cave for nearly five hours. We were tired at the end of the drive home, but happy that we had this opportunity to see the cave where Indians, and later Army deserters and outlaws, had found refuge.

After our short but pleasant holiday, we settled down again to the daily routine of work, but it was a pleasant memory. Now there were three families of what were generally called "Dutchmen" by the natives, and they still were all working hard to build up their places, and grow all kinds of fruit and vegetables. This was regarded by many as a sheer waste of time and energy. They had lost faith in the land their forefathers had settled on. Many families who had lived on a place for years had not a tree, vine or garden patch to help provide a change in the daily diet of hog-hominy and corn bread.

Something had happened to the generation who tilled the soil now. Somewhere along the way they had lost the ambition of their forefathers; to reclaim the wilderness and forge ahead. Sufficient for the day was their motto, why worry about tomorrow? Perhaps too many poor crops due to droughts, and too much hard work to pay for the scant reward in any but the most necessary undertaking, had gradually caused them to lose their ambition, and a lack of interest in what went on beyond the shelter of the hills, which many had never been beyond. After the end of the Civil War; they were left far behind.

A typical way of their living was seen all around. Their house was near a spring for water, usually a log house with a stone fire-place, and a porch of rough boards in front, and a lean-to kitchen in back. Maybe there was a window in each room, maybe not. A hopper made of slabs graced the side yard. This contained ashes from the fire-place. The lye which was used in making soft-soap, was obtained from the water that drained through the ashes into a can or tub. Mixed with waste fats it made a strong, grayish soft soap for household purpose.

A log building served as a smoke house, for smoking and storing meat in hog killing time. It was also used as a cellar. The hams, shoulders and side meat were salted and packed in boxes, or put down in brine until spring. Then it was hung from rafters and smoked over a slow fire of hickory wood. A hen house and corn crib of logs were some distance from the house. Any number of log barns were to be seen on some places, in various stages of decay. When a barn was so filled with manure that the horses no longer could get into them, instead of cleaning them out and putting the manure on the starving land, they simply built another barn! Small wonder that the soil was too poor to grow crops.

A place not far from our claim was an example of this, lets call it, discouragement. Altho Ben had lived on this place for many years with his family, there was no garden or fruit, except for one large plum tree to be seen. Ben stopped by one day while looking for a strayed cow, and he was quite surprised to see how much we had accomplished in the few years since we had come. He told us if we wanted some plums to come down to his place, as they were all going to waste; his folks did not pick them. The next day I trudged along the trail and across the big road carrying a big basket loaded with green beans, beets and other vegetables. Ben’s wife and her mother, who lived with them; were sitting on the porch. They were glad to see me and did they ever drool over the vegetables!

We sat on the porch for a time while asking me about the family, they watched the big-road, and wondered who was passing, where they were going and why. This and piecing quilts was about the only interest they seemed to have. When we went into the main room of the house, I noticed the many quilts all folded and stacked on both sides of the fire-place on shelves. They were quite pleased to show me some of their work. There must have been two dozen of them, all were beautiful in design; every stitch was perfect. They showed me the plum tree and I filled my basket with fine plums. They were large and sweet; and I could not understand why these people would let such fine fruit rot on the ground. There were many families like them, while others were trying to better their way of life and make their places into homes, with fruit shrubs and flowers, instead of having just the bare, rocky yards, with not even a blade of grass.

Most folks had old fashioned furniture, which

14

had been brought along from former homes. Spool beds and split hickory chairs were common, and many a bureau or center table would be considered a priceless antique today, was found in some early settler’s log house. Many of the women could knit, and their counterpanes were really beautiful. Rag carpet covered some floors. Pictures hanging on the wails in dark, heavy frames, were mostly of men, with full beards, often in uniform. The stern expression on their face was probably caused by the high tight collars they wore. The women were dressed in high-neck long-sleeve dresses; with flounces, ruffles, braid and bows. A wedding picture would show the groom seated in a carved high-back chair, with the bride standing with her hand on his shoulder. These treasures were probably their only tie with the past.

Some housewives put up peaches for winter, using jugs. How they got them in, or out, was a mystery. Peaches grew well here, and if a newcomer wanted to buy some, they sold for ten cents a bushel. Being so far from the fast transportation it was not possible to ship any perishable fruit, so many let the hogs feast on what ever fell from the trees.

Many did not cut down the trees when clearing for a field. They cut down only the best trees to split enough rails to fence the field, and just chopped around the trunk of the others for a depth of about a foot, and at least four feet above the ground. In a few years leaves no longer came out of the branches in the spring, and gradually the tree died. There they remained in the fields like gaunt skeletons, with their bare branches, like imploring arms flung toward the sky. Years later when they fell over of their own accord, they were hauled out for fire wood.

Some families had only a few milk cows, other stock ran on the range the year around. In winter a quart of cottonseed and the dry grass they foraged for, carried them through the winter. The cattle, like the horses, were hill stock of mixed breeds. The cows did not give gallons of milk a day, like the "contented cows" we have today. There were new calves in spring, which could be sold when yearlings, to drovers for cash. Hogs were the tough razor back breed. They were long, tall and narrow when grown, their heads ended in a snout over a foot long. They had to root in the woods for most of their living. Only when the weather was cooler and "hog-killin" time was near, were the chosen ones penned up and fed some corn. If one liked streaks of lean in the side meat, a day of corn feeding was skipped, it was also claimed that if meat curled up in the skillet when frying it, it was because the hog had been killed in the wrong moon. How true this was we never did know. We had always planted by the moon; rooted vegetables in the dark, and those that bore on top of the ground in the full moon. We had never heard that meat was affected by the man up there whom we are now shooting rockets at! But live and learn. This season was always a busy one for the women folks. Lard was rendered and put in crocks. Head cheese, or "souce" as some called it, made mostly from the head and ears, with spices added was cooked and poured into pans. When cold it was a firm cake; and delicious. And if there is anything more tasty than back-bone and young turnips, greens and all, I have yet to find it!

Cattle and hogs were marked by the owner by what was generally recognized as his mark, just as ranchers branded their stock in the west. Here the marking was done by cutting notches of various size and number, into one or both ears of cattle and hogs. It was often suspected that some people were not above taking hogs that had not been marked if they could get by with it. They maintained that any hog over six months old, not marked, could be claimed by any one. There was a tale told about one man, who had a rapidly growing herd, and his mark was both ears cropped off close to the head. This, of course removed any other marks. One fall a widow of 70 was reported to the court on a charge of hog stealing. In winter we often found a big bed of leaves in the shelter of thick brush, where hogs running loose, kept warm in cold weather. It was a sort of community affair; and often big enough to accommodate fifty or more. It was amusing to see them gather leaves by mouth and carry them to add to their bed.

Fall came with frosty mornings, the woods as usual a riot of color. As winter came we enjoyed making huge pans of candy, using sorghum and roasting peanuts to make brittle. Sorghum was called "long sweetnin" here and sugar was "short sweetnin". We fared better, and had less worries that winter than ever before. Little did we know what the New Year, now rapidly approaching was to bring us. Perhaps it was better that we could not see ahead.

The winter and following spring passed as usual; and the early summer brought a real drought. The heat was now terrific. Many people, who had given up hope time and again, to have faith renewed by the miracle of rain coming in time to prevent a total loss of crops, now gave up. They just loaded the few possessions they had room for in the wagon, disposed of their stock, closed the door and left.

Many went to Oklahoma where they had kinfolks, and hoped to earn enough to live on. Henry and Mr. Muller went to Kansas, where they were

[15]

hired to work in coal mines. A brother of Fathers had sold his farm in Iowa and moved to a locality not far from several fair sized towns. Sister Anna had left in early summer and after a visit with the family, she and a cousin her age had gone to a town and were working together. All we heard every time someone dropped by was how many more were leaving. Someone had pushed the panic button, but good.

Father had promised Henry he would stay on the place at least until he proved up on the land and had a deed. Mother was constantly urging him to go up-state where his brother was located. If he was going to make pipes again it was better to be close to a market. His brother had offered him the use of a log house on the place, where he could live and have a shop. Father had at last reluctantly consented to try this for a year, but insisted that he would come back when the time came to prove up on the place. We were to remain there as John and I could take care of the stock and what planting we would do the next spring. We were lonely, but made it through the long winter.

In spring we put in the garden, and a patch of cotton. The remainder of the ground was planted by Mr. Muller in corn. He also trimmed the grape vines; and was to have the grapes except what we needed for jam and jelly. Our peach trees, were all loaded with big peaches, and we dried them by the bushel. We cut them in half, took out the seed, then laid them on boards side by side, covered them with netting. When dry on one side the halves were turned, this was done until they were perfectly dry. It took a lot of peaches to make a bushel of dry ones, but we kept at it until we had a two bushel sack full. Our fingers were so stiff that we could hardly bend them by the time we were through with the crop. But we had nothing to do, and it did make time go faster.

Our friends, the Antons, had built a new house that summer, and gave a dance as a housewarming that fall. It was the first time I had ever been to a dance in the hills, since we were friends I was allowed to go. There were two brothers who played for dances, and they were present with their battered looking fiddles. Neither one of them could read a note, but if they heard a tune once could play it by ear. Corn meal was sprinkled on the floor of the living room to make it smooth, and a good caller could be heard over the din and "Turkey in the straw", or other old tunes suited to the square dance.

I stayed for the remainder of the night after the crowd left in the late hours, walking home the three miles the next day. This was the first time I was at any gathering in all the years we lived here. We heard of the fish-fries and revival meetings occasionally, but never went. As a girl once said, "I didn't went, I didn't want to went, and if I had wanted to went, I wouldn't have got to goin".

Time passed slowly, after all the years we had been so busy it was a let down. The most exciting event was when I brought home a letter from the Post Office from Father.

Finally we received a letter saying he would come to prove up on the place in late October. We were to have the necessary six notices of intent to do so, published in the weekly county paper at the proper time.

One morning in August we heard a horse coming down the path, and saw that the rider was the Anton son Bill, riding their big gray horse. He looked as if he was ready to drop. Mother asked him what was wrong, and he replied sadly, "Father died last night, and he will be buried this afternoon". We were shocked, as we had not heard that he was ill. Bill drank a cup of coffee; and rode on to inform the Muller family of his sad news.

We hurried, taking care of only the most necessary chores, dressed and walked the three miles to the home, where we found the Anton family still unable to realize what had happened. There were no undertaking parlors nearer than the County seat, so burial must be arranged as soon as possible, as the weather was hot in fall.

Word had been sent to the man who made the coffins, they were made of rough oak boards, planed, then covered with black sateen, and the inside lined with white muslin. These items were always on hand at the local stores. Others would get word to open a grave in the cemetery nearest the home; every one was helpful in time of sickness or sorrow.

After the men arrived with the coffin, the body was placed in it, and the lid fastened. Then it was carried to the wagon and covered with a patch-work quilt. We rode in another wagon with the family, followed by a few more wagons, and more people on horse back. After what seemed an age we turned off the road into the cemetery.

It was a bare, sloping piece of land without a tree or shrub. A few boards marked some of the graves, some were only sunken spots in the earth. A grave had been opened by the time we arrived, it had been hard digging in the dry, rocky soil. A school teacher, Mr. Golden, who sometimes preached at meetings was there to hold the services, and about six women would sing. The coffin was now beside the grave and services began. After Mr. Golden had made the eulogy, the women sang a hymn, followed by a prayer. Then the final hymn was sung. I have never forgotten the chorus of this hymn. It was "Only a

[16]

dream, only a dream, and awaking beyond the dark stream, how peaceful the sleeping, how joyous the waking; for death is only a dream." As I had never attended a funeral before, but had seen the black hearse and the carriages moving slowly along to the well-kept cemetery in Illinois, this funeral seemed so bare and harsh.

Returning home with the sad family, Mother decided to stay overnight. As dusk had fallen John and I started for home. It was not too bad as long as we were on the big road, but when we left it to cut through the woods, we quickened our steps. Every time an owl hooted we walked a little faster, and finally made it home. The dogs were happy to see us, and after feeding them, milking the cow that had lain down by the barn, and closing the chicken house, we decided we were too tired to light a fire and get any supper, so we went to bed. Tired as I was it took me a long time to get to sleep. I could not forget this long day.

Little did we dream that we too would soon be left without a father, but less than a month later, as we were counting the days until his coming, I brought home a letter from the Post Office. It was from our uncle, and he wrote to tell us that Father had died suddenly, after only a few days illness. Before the letter could reach us he had been buried. It would have taken us three days by wagon and rail to reach Uncle’s home, and he knew we could not make it in time, so he had to go ahead with the funeral. This locality ‘tho further advanced than the Ozark hills, was not near any undertaking establishment. Uncle had to drive twenty miles to the County seat, where a furniture dealer sold coffins. On inquiring Mother was informed that the three notices of intent to prove up on the homestead filed in Father’s name would be allowed, and she would only have to file the remaining three in her name. We made arrangements to leave, as we three could not run the place and make a living alone. Our Sister and brother who were upstate had found work there; and did not want to return. So at the end of the three weeks added notice of intent to prove up on the claim, Mother went to the County seat. The necessary papers were recorded and she was told that the deed would be sent from Washington, D.C., in a few months time.

We had looked forward to this trip out into the world we had left nearly six years ago, but now it was a sad and troubled journey. We soon found out that life was not all sunshine beyond the hills, and we all, except John, had to find work so we could help pay bills due to Father’s death, and help out when needed.

After a long wait for the deed to come, Mother was informed that the three notices published in Father’s name had not been allowed, and she would have to return to the place and file six in her own name, before a deed would be sent. This was quite a blow, but if she did not return and live there a certain length of time, then publish the notices again she would lose the claim.

So she and John returned to the hills, and after a time the deed signed by Theodore Roosevelt was sent to her. She and John lived there for about three years, then sold to a man from the north, who fenced the place, but never did live on it. All the hard work we had done was wasted. Later on we heard that it had gone back to the Government.

After selling the place the rest of the family migrated to the Puget Sound country of Washington state; where work was plentiful in the woods and mills.

Since the earlier years of the 19th Century, life in the Ozark mountains has changed beyond all belief. At last the long-awaited railroad, the Missouri Pacific, built a road connecting Kansas City and Little Rock in Arkansas. This was what the country so long dormant had needed to awaken it. Then Powersite Dam was built on White River, and Lake Taneycomo was formed, the purpose being for power and flood control, it was finished in 1941. More recently Bull Shoals, also on White River, and in both Missouri and Arkansas, also for power and flood control was completed. Since the railroad came through Hollister, near the County seat, many of the older residents moved into that part of the county. Many newcomers also started up in business in towns near the railroad, and the way of life was improved for everyone young and old alike.

This great change did not take place in just a few years. It took time and money to build highways and improve side roads. The day of the rocky dirt road was past. Automobiles and trucks now follow the winding paved road. The wagon yards, blacksmith shop, and bunk-houses are all things of the past.

No longer must one depend on kerosene lamps and wood stoves in winter’s cold and summer’s heat. Wells are dug where springs were once the only source of water. Now modern homes with bath rooms; have taken the place of the bench, with its tin basin, crash towel, and bar of "Granpas Wonder Tar Soap". The mid-wife on horseback with her satchel, is no longer seen on the trail, racing the stork. Now there are Hospitals and rest homes, with competent Doctors and Nurses to look after every need. There are telephones that bring help fast, no waiting ‘till a rider can go miles to summon aid for the sick and injured. Surgery is no longer preformed on a

[17]

table in a cabin home, by the light of a lamp.

Now there are modern Mortuaries to serve the dead, well kept cemeteries for their final resting place, and granite markers instead of boards. Flowers, trees, and shrubs make them a spot to remember, not a place one wishes to forget. Churches of many denominations with ordained Ministers to hold services, are in many locality. Schools are not so far apart, and ,now hold full terms, and have more classes where more subjects are taught. Colleges include the School of the Ozarks.

The growing generations, if they have the desire, now also have the opportunity to make something of their lives. They no longer need drift from birth until death without any knowledge of life except that once bounded by hills. Perhaps this great transformation would have started many years ago, if conditions had not been so hopeless. In these days there were few pensions, no Social Security, F.H.A. loans nor much help of any kind.

The only time hill folks knew there was any interest in them or their lives, was when someone was suspected of making "Moonshine" whiskey in some hollow, and selling it without a Government stamp! All changes did not come at once, it took time for the tide to change from low to high, and above all faith and patience by the people that this country was redeemable, if given a chance, and some aid by those in the world beyond the rolling hills.

The Ozark region is now one of the most beautiful vacation spots to visit from spring to late fall. Fishing in streams and lakes, riding forest trails and visiting the places of interest, among them old Matt’s cabin and Marvel Cave which are mentioned in the book, "Shepherd of the Hills". Access to them is easier now, than years ago.

Many resorts have sprung up around the lakes of pure, crystal-clear water, made by the two large dams, State parks with trailer camps, all well-kept are available for those who prefer them. Hotels and Motels with the best accommodations, golf courses, tennis courts, and archery ranges for those who prefer these sports, make this a happy vacation land. There are now over 2,000 recreational facilities in this region.

Modern homes and ranches are to be found, where the old log house once stood. Pure-bred cattle, hogs and other stock graze on the land where the mountain cattle and mules once wandered far in search of better grass and water.

The natural Beauty of the Ozarks has not changed, wild flowers bloom in spring, and the woods turn a riot of colors in fall. Birds sing and crows are busy chasing hawks: cawing wildly when they get one treed. The buzzard soars in the sky when they scent a lifeless animal. Lizards rustle through the dry leaves, and wild life goes on as usual in many places not in the midst of the new civilization. Many old homesteads are deserted and covered with brush and second-growth timber, since owners left.

The wars took many of the younger men to other parts of the world, that were at this time further advanced. But there are still many descendants of the old settlers living in the hills, they probably agree with the old-timer who once remarked: "When God made the world, He must have taken everything he had left over, the hills, streams, forest, and rocks, tossed them into a pile and so made the Ozarks." God must have had a lot of beautiful things left over to create the Ozark Hills.

I have an item written by a school-girl, dated on March 7, 1940. It was about a trip to the place we had lived on 68 years ago. She wrote: "We had beautiful spring weather during the time the Cedar Creek School went on a field trip. We went to the place where Mr. Gerten used to make clay pipes. We gathered a collection of what we found, parts of clay pipes, snails, beautiful rocks, cocoons and also some flower roots. We set them out in our school yard." We gathered some fine flint arrow-heads; when we lived here, left by the Osage Indians, now children gathered broken pipes left by the "Furriners" who had also departed! Time goes on.

Some ten years ago my older brother and his wife made a trip to the Ozark country. They drove over the old side roads, after leaving the highway, to see if they could locate the old homestead. They finally found it. The land we had cleared was all overgrown again, there was no trace of the fences, orchard or vineyard. The buildings had long since disappeared, but they did find some of the stone walls that we made so many years ago. They seem to stand as a monument to the vanished "Furriners" who built them in the long ago. May they stand forever!

While this section of Southern Missouri and Northern Arkansas has grown beyond belief since early in this century, evidently the big gain in growth and prosperity has overlooked other sections in the rush of events. These spots have gone down; and need help to get back up, and going back up takes more time and effort.

The articles in newspapers recently: that the lower Appalachian region is about to receive much needed aid from the Government, is of interest. It does not seem to be lack of highways, but lack of schools, and means to support them that has been the cause of much hardship here.

Good roads bring a certain amount of tourist trade to a community. But there must be money and experience to build facilities, and people who

[18]

know how to manage them. People from outside, people who have the advantage of education, though they may not have attended any college.

Helping to fix up the homes, often tumble-down log houses with sagging porches and bare yards, and nothing beyond the most necessary utensils and furniture inside, will not be enough to restore the pride and incentive of their ancestors, who often had little more when they came as pioneers to the mountains or prairies. Aid from the Government would not bolster them for long; after it was no longer considered necessary, they must want to insure that their descendants have a better life.

Schools should be given priority over everything else. They need not be the architectural show place that so many newer schools are, but should have a staff that can understand how a student can be a big boy or girl and not able to do the work of younger pupils as well.

In many sections of the country, children are more apt to drop out of school at an earlier age, because their help is needed at home, no matter how little they can do or earn. Not because they want money for cars and other means of pleasure, as is so common today. Many younger children go only part-time. They often have not clothes or means of transportation for the full term. Many of the children in the past, and many in the future, will go to school with more patches than the original garment showing, bare-footed and with a scanty lunch. Often when they see others with a tasty lunch, they wait to eat theirs on the way home. (I did this myself many times).

While better living conditions, shoes and clothes, even made-over ones, will help keep younger children in school, it is not enough. With the mechanized age that is here there must be a way to train the older pupils, the ones likely to drop out. Years ago; the person who could not read or write, did not have much chance of success, now the three "Rs’ are not enough. Manpower must be trained today.

The part of the Appalachian country that was strip-mined, would probably need attention if it was expected to grow some of the food needed. Worn out land is not able to produce enough to pay for seed and cultivation.

Nor can wishful thinking do any good, which reminds me of a story my Father told of the old country. To possess a piece of land; even a small patch, was something to be proud of. It gave one status. The smaller the patch, the more it was treasured. In late winter it was customary to have a procession of all the owners, and they went from field to field, singing and praying for a good crop. They had come to a sadly neglected patch of ground, and one old farmer said, "Here helps no singing or praying, this field needs manure’. So perhaps the neglected land in this part of the country should be included in the list of what might help the people, and encourage them to help themselves. Let us hope it will not take as many years to bring better days to the folks in this region, as it did to the homesteaders in the Ozark hills.

In a time of disaster, be it famine, fire or flood, this country is among the first to aid the people that need help. This is noble and good, but the slow disaster that creeps slowly and unnoticed through a section of country for years, can cause as much suffering and loss as one that strikes swiftly, and help is needed just as badly.

It has been said that there is no need for any one to go hungry in this country, maybe it is too close to home to be found, like the tale about the man who once searched far and wide to find a four-leaf clover, and failing to find one returned home. There he found one growing in his own back yard!

Many worry about the men and women that are confined in prison for various crimes. Many reforms have been instituted to make living conditions better for them, and to teach them trades, so they have a chance to make an honest living when they have served their sentence and are back in the world again.

The people who are confined to a section where only hopelessness and hardship thrive, are charged with but one crime—poverty. Many have served a life sentence for this, with little hope up to now of a parole. So let us hope that at long last these prisoners of poverty will be given a chance, and that their descendants that will profit from the aid, will enjoy a better way of life. Although perhaps too late to help their parents, aid now can help the growing generation to enjoy the reward of a good education.

The End

[19]

This volume: Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues

Other Volumes | Keyword Search | White River Valley Quarterly Home | Local History Home

Copyright © White River Valley Historical Quarterly