Volume 1, Number 10 - Winter 1963

Origins of a Missouri Rural Teacher

by Percy Bridges (as told to Gene Geer)

For one who was destined to spend thirty-five of his adult

years as a teacher in Christian County, Missouri, my first day in school was

not a promising beginning.

The year was 1898. I had just passed my sixth birthday. The school, called Nubbin Hill, was located a mile across fields and gullies from my parents log cabin. This cabin was on the Uncle Dick Elkins place a mile east of the Chadwick branch Frisco station called McCracken, or five miles east of Ozark, the county seat. Our home overlooked the railroad track and a dirt country road.

The reader should picture a healthy, free-roving lad and his younger brother, Bert, then four years of age, who was permitted to attend school although not as a regular scholar. By going to school with me, so Mother and Father decided, Bert would ease his own lonesomeness at home and at the same time make it easier for me to adjust to school discipline. We had a younger brother at home, Charley; but he was only two and didn't count as a playmate able to keep up with our fast pace down the fox and rabbit trails.

We are trudging down the hill toward the distant school, me toting the gallon molasses pail in which our mother had packed our lunch. We were not thinking about the long sentence of school attendance ahead. We were talking about our play plans which school would interrupt. Also, we were rather fearful of the new experience, the strange teacher and the strange ways of older and possibly unpleasant pupils which we would have to cope with, as well as the process of learning, also new to us.

In time, of course, I learned that the teacher, Jim Bruton, was a kindly man and that we could easily fit in with the school regimen as well as with the other pupils, who were much like us. Time also brought changes in me so that I came to look upon school as a great adventure.

In those first few hours, however, we looked about with growing restiveness at a scene in which we did not seem to fit. Nothing was done to ease the apprehensions of new scholars. There were about forty pupils all told, varying in age from four to twenty, gathered in from the surrounding farms. Mr. Bruton called each class forward in turn, where after preliminary name-taking the pupils recited the lesson in sing-sang style. All of it was meaningless to Bert and me. So, when the short recess came at about half-past ten, I picked up our lunch bucket, called a "let's go" to Bert, and back down the holler we headed for home and the familiar, sure that we had put our school days behind us. The folks were working in the field beyond the cabin, so Bert and I sat down on the grass beneath the giant oak tree shading our house and were disposing of the contents of the lunch pail when Father and Mother came in and found the truants.

It was a day when school attendance was not compulsory. By many of our elders, who had managed with little or no education, school was regarded often as a soft way to get out of work, as a waste of time, as a means of alienating the young from the social and religious traditions of their families, at any rate as necessary only to the extent of learning how to read, write and cipher. Rural schools then began in July and closed by the new year. In this period came such farm tasks as corn picking, sorghum making, getting in the winter's wood. If the pupil's help was needed on any of these chores he was withdrawn from school until another spell of comparative leisure on the farm. In short, school was a luxury to be indulged only when more important things were not pressing.

My parents did not go this far. They wanted. their children to get all the education possible in that time-for country people usually graduation from the eighth grade. Hence it was that on that first day my father walked us back to Nubbin Hill after noon dinner, explained the situation to Mr. Bruton, and asked him to see that we behaved.

To my parents, who had received their scanty schooling in log structures in a few three-month terms, Nubbin Hill was a "modern" school. Built of native oak, it had three windows on each side, two doors in the east front, and a belfry on top. Two rows of seats, one on each side of a center aisle, were double so that an older brother or sister could sit with a new pupil, or a classmate could also be a seatmate and share his slate with you, or a well-masticated piece of chewing wax. Beside each door stood a water bucket with its dipper. On warm days the teacher excused an older pupil or two, who took the buckets to the spring in the holler, brought them back full of

[6]

cool water, and passed them around amongst the pupils for each to drink in turn. A square, wood-burning stove in the center supplied heat in the cool months. Up front the blackboard faced the room beside the teacher's desk and chair.

Percy Bridges, his wife May, and their granddaughter Peggy Jean Melton, 5, standing before the Bridges' new retirement home in Ozark, Mo. Mr. Bridges retired in 1962 after 35 years as a teacher in the rural schools of Christian County, Missouri.

Our landlord, Mr. Elkins, had a substantial frame home to the west of his tenant cabin where we lived. Our home, neither better nor worse than most other tenant cabins, consisted of one big room, made from logs, the spaces filled with slabs and chinked with clay. It had a door on the east and a small window on the west. The floor, of wide puncheon boards kept clean with wash-day lye water and elbow grease, supported our home-made table, four splitbottomed chairs, two large beds and a trundle, and a combination box cookstove and heater, with its pipe thrust through the roof of shakes. On the overhead beams were laid some planks, thus providing storage space for excess bedding, clothing, vegetables and the like. Our water supply came from the Bray spring across the road.

A log barn about 14 X 16 feet in size west of the house was our only outbuilding. If any space was left after hay and grain storage, it was occupied by our team of horses, two milk cows and their calves, the brood sow and her pigs, or the flock of laying hens. Otherwise they had to take the weather as it came. There was a rail-enclosed garden spot northwest of the cabin where Mother raised our eating vegetables, and beyond lay the field where Father tended feed for both animals and humans.

We never ate high on the hog; neither did we go hungry. In the summer we ate chicken meat, eggs, fish and fresh vegetables from the garden. At the first frosty spell we butchered a hog or two and salted down the meat. Mother preserved grapes in sorghum, dried apples and peaches, and put up wild berries and vegetables in tin cans sealed with wax. We raised a patch of sugar cane to be processed into sorghum for our principal sweetening. Every two weeks Father filled a sack with a "turn" of corn, slung it over the back of a workhorse, and rode off to Uncle Jack McCoy's grist mill on Bull Creek. This provided for our bread and cakes. There were large jars of kraut in the cellar, their lids held under the brine with scrubbed rocks.

I have described the first of our homes that I can remember. As a tenant farmer, my father moved every few years to a new place near Sparta, always hoping eventually to have a combination of good soil and good year so that he would net enough to buy a farm of his own. Yields were generally low and prices lower. It was not until I was a boy of fifteen that my father had accumulated the purchase price of some rough land on Bull Creek. This was in 1907, and my parents were approaching middle age.

As tenant, Father furnished his labor, work animals and implements, and paid a rental of one-third of the hay and grain raised. By animals I mean a team; and by implements I restrict the term to a plow, rake, harrow, double-shovel, and a wagon. Binders, mowers, and combines were in the future. Seeding and gathering of crops for all but the better-off farmers were done by hand, with cradles, hoes, hand-seeders, corn knife and pitch fork.

My chief memory of my parents is of their cheerfulness in a world bounded by hard work and what to us today would be privation. They did not consider themselves underprivileged, however. They had not been made aware by the growth of creature comforts in recent generations that they were suffering because they lacked electricity, refrigeration, a car, and a TV set, as well as an education, books, magazines, pictures and music. They had what most of their neighbors had: freedom in the big outdoors, family and friends to converse with, enough to eat and wear if they hustled, occasional get-togethers such as parties, pie suppers, and revivals. Lacking libraries and symphonies they kept alive by recounting them the brave deeds of legendary heroes, the exciting tales of neighborhood feuds and their resulting violence, and always the twice- told accounts of the not-too-distant Civil War and the activities of guerillas and bushwhackers who made the border country of Missouri, Arkansas and Kansas a dark and bloody land.

[7]

My father's people came from Tennessee and Alabama, migrating to Missouri in the 1840's. Grandfather George W. "Wash" Bridges worked as a teamster for a U. S. government contractor when St. Joseph was the taking off point for Army outposts in the West. Grandmother Bridges, born Nancy McDaniel, was as a girl employed as cook in a Springfield boarding house. She spoke of having served General Nathaniel Lyon prior to his death at the Battle of Wilson's Creek. General Lyon, she said, complimented her particularly on her cookies.

My mother was a McCoy, daughter of Captain John McCoy of the Union army. Captain McCoy, born 1820 in Tennessee, came to the Bull Creek country in what then was Taney County in 1838, making the journey by ox cart with his parents. Later, following his marriage to Elizabeth Jones of Taney County, he moved back to Tennessee, then on to Newton County, in Arkansas. Here he represented his county in the State Legislature, was commissioned a captain at Fayetteville in 1863, and the next year resigned to take a seat in and be chosen presiding officer of the rump constitutional convention representing the twenty three North Arkansas Union counties. One of the stirring tales which excited us as children was that of Captain McCoy sheperding a caravan of emigrants from the wasted lands of North Arkansas through bushwacker-infested country on his return to Bull Creek in 1865.

Both Father and Mother had prodigious mem ories for the tales arising from this colorful family history, as well as for the songs they had learned in childhood and for the topical ballads by which the pioneers, like 19th Century troubadours, kept alive and re-told the tales of derring-do current throughout the area. It did not embarrass them in the long winter evenings about the fire to sing these songs for us children as well as for any neighbor who happened in.

One of my pleasant boyhood memories of my ever-busy mother is this: it is crisp autumn and the cookstove sends a glow of warmth through the crowded cabin. In the center of the room Mother is seated in a hickory chair, both hands occupied with knitting pulse warmers, or wrist mittens, for her family against the coming winter. One foot is on the rocker of the home-made cradle in which Baby Charley lies, and she keeps this in gentle motion with her foot as she croons a melancholy ballad:

-

"Twas in the merry month of May

When flowers was a-bloomin';

Sweet William on his deathbed lay

For the love of Barbara Allen.

Mother did not realize that the origin of the songs she sang often went back to a distant past in the British Isles. She had learned them from her mother and grandmother. Meanwhile, Mother also had an eye out for the cookstove fire which must now and then be replenished from the stack of wood behind the stove, for the pot of beans and fat pork stewing on top the stove for her family's dinner, and for the welfare of her older children playing outside the door.

Sometimes Mother's song was a hymn. I recall in particular that she often sang in a low key while busy over the cookstove a favorite at the "protracted meetings" and brush-arbor revivals: "I'm Bound To Live in the Service of My Lord." She also favored a frontier ballad called "The Dying Cowboy", possibly because it had the rather melancholy tone preferred in a song, partly also because it was a favorite of her husband's. Mother had a clear, throaty voice and it was a pleasure for all of us to hear her sing.

Father preferred the more rousing tunes: Civil War songs such as "Marching Through Georgia" or "Brother Green"; the plantation song "Shortnin' Bread" from the deep South; or topical ballads retelling a well-known event such as "The Berryville Prisoner" or "Texas Rangers". Father was full of tunes, most of which I learned by heart from his repetitions. Many Missourians, like my own family, fled from Arkansas in the harsh days of Civil War and Reconstruction. Some of their feeling for that poverty-stricken area was expressed in the following balled I learned from Father. I have never seen it in print:

My name it is Bill Stafford;

I was born in Buffalo town;

For nine long years I've rovered;

I've traveled this wide world 'round.

It's many ups and downs I've had,

and many a hardship saw;

But I never knew what misery was

till I went to Arkansaw.I landed in Van Buren

one sultry afternoon,

Up stepped a walkin' skeleton

and handed me his paw,

And invited me down to his hotel,

"the best in Arkansaw."

Next morning I rose early

to catch an early train;

Says he, "Young man, you better stay,

I have some land to drain;

I'll give you fifty cents a rod,

your washin', board and all;

You'll find yourself a different man

when you leave Arkansaw."

[8]

I stayed six weeks with the great big bloke

- Thomas Howard was his name-

He was six feet seven in his boots,

and as slim as any crane;

His hair hung down like rat-tails

o'er his long and lattering jaw;

Begod he was a photygraph

of the gents in Arkansaw.

He fed me on corn dodgers

as hard as any rock;

My teeth began to loosen,

my knees began to knock;

I got so thin on sassafras

I could hide behind a straw;

Begod I was a different man

When I left Arkansaw.

Yes, he fed me on corn dodgers

and his beef I couldn't chaw;

And he taxed me fifty cents a meal

in the State of Arkansaw.

The day I left that region-

I dread the mem'ry still-

I shook the boots all off my feet

with an old Arkansaw chill;

I staggered in to a saloon

and called for whiskey raw,

And got as drunk as billy-be-damned

the day I left Arkansaw.

Now I'm working on the railroad

at a dollar half per day;

And I intend to work on

until I get my pay;

Then I'll go to the Indian Nation,

I'll marry me a squaw,

And bid farewell to you swamp angels

who live in Arkansaw.

If ever I see that land again

I'll give to you my paw-

It'll be through a telescope-

from Hell to Arkansaw.

For us children, though, nothing was as larky as the folk tune, "Fiddle I Fee". This required not only a talent for mimicry, it also called for verbal agility, a rapid fire repetition of each familiar home and barnyard sound in turn as they accumulated, all tied to a simple verse:

Oh, I had a bird and the bird pleased me,

And I fed my bird under yonder tree,

And the bird went (whistle imitating a jaybird).

The reader can imagine the clamor which aroused the mirth of the youngsters by the time Father was nimbly repeating the whistle of the jaybird, the bark of a dog, the meow of a cat, the quack-quack of a duck, the moo of a cow, the bray of a mule, and the "mammy, mammy" of a baby, all in rapid succession as the song gathered momentum, only to taper off on that quiet nonsense ending, "Fiddle I Fee".

In reading, one's enjoyment of a tale is limited by the style and imagination of a single writer. Lacking many books, we of rural South Missouri in the early years of this century sopped up open-mouthed the tales of local origin heard at our own hearth, in the homes of neighbors, or around the potbellied stove in the country store where we did our "trading". In the telling, each recounter injected the flavor of his own personality and idiomatic speech into the event recounted.

Since the climax of the Bald Knobbers history occurred within the experience of our elders, and since the Green and Eden families near Sparta who suffered the final indignities were known or related to most of us, that story was heard in all its grim details.

Closely related to the above were the treacherous murder of John Melton and Jimmy Cox during Marmaduke's raid toward Ozark and Springfield, the depredations of the sadistic outlaw, Alf Bolin, the tragic death of 17-year-old Minnie Cash, and John West Bright's murder of his wife. The reader can see that although we lacked the sensational tabloids of today, we did not lack for the subject matter which keeps them going.

Within our immediate family we had many a stirring tale to tell. Of these possibly the most tragic was the murder of Grandfather "Wash" Bridges. In 1870, or during President Grant's administration, Grandfather and Grandmother Bridges moved to a farm they had bought five miles east of Yellville, on Crooked Creek in Marion County, Arkansas. North Arkansas had a majority of Union sympathizers; it also had a rash of lawless characters Who took advantage of reconstruction disorders and a dearth of local law enforcement to prey upon honest settlers. People then did not entrust their spare cash to banks; they concealed it about their homes or their persons. This fact enabled many a desperate character to live without labor.

Near my grandparents' home lived a surly family dominated by a burly, hard-eyed father and his eldest son. They seemed affluent although they did little on their farm to earn a living. A series of robberies in the area were connected to the father's and son's furtive comings and goings; but so fearful of these men was everyone that few would voice their suspicions. The most outrageous of their crimes was the killing of a stockman who rode off with $800 on his person and was found dead, minus his hoard, the following day.

[9]

Grandfather came within range of the family's bitter guns in this way: One day shortly after the above robbery, on the search for a strayed calf, he stopped at the home of this family to inquire if anyone had seen the animal. Behind the smokehouse, under a tree, he came upon the father, son, and a neighbor boy counting and dividing their loot. Grandfather pretended not to notice what was taking place and asked about his calf. The hard-eyed neighbor came to the point at once. Knowing that he had been discovered, he offered to cut Grandfather in on the deal. Grand father refused and left; but he was thereafter a marked man.

He was a big, fearless man standing six feet four and was inclined to ignore his danger; but Grandmother insisted that they leave and return to Missouri when safety lay. To quiet his family's anxieties, my grandfather rode off horseback one day, headed for Missouri where he had friends. He was followed at a distance by his neighbors. He stopped for the night at the home of an acquaintance named Anderson. After dark there came a knock on the door. The door was opened on the burly neighbor, his son, and the other boy. Representing themselves as officers of the law, they said they were pursuing a runaway felon and gave a description of my grandfather. Grandfather, carrying his rifle, went outside to parley with the men and was allowed to return to the house. That night he slept close to his rifle and next morning rose early and took a direction opposite to the hoofmarks in the road. He was headed off nevertheless. The desperadoes got Grandfather and his horse in a line between them, the father riding ahead, followed by Grandfather, then the son and the other boy. On the way into the hills Grandfather was shot from behind. Spurring his horse, he made a bolt for escape but was shot in the forehead by the father, who wheeled at the sound of the shot. His bones were not found until a year later, when slow justice got around to a court hearing.

Grandmother Bridges thus in 1876 was left a widow with a farm and four small children to care for. One of these was my father, also named George W., then a tot of four. For another eight years Grandmother carried on a desperate battle for survival, but apparently the neighbor family was still determined to drive the Bridges from the country. One night she awoke to the crackling of burning lumber and found the cabin on fire. She got herself and children to safety but was unable to save much else. Some kind people in Yellville took in the family until they could arrange their return to Missouri in a caravan got up by other emigrants from the hostile land. My father by then was a strong lad of twelve, able and willing to make his way in the timber cutting which was the principal activity in the virgin country of southeast Christian County opened up by the coming of the railroad to Chadwick.

My brother Lonnie (now eastern judge of the Christian County Court) had been born in April 1899, while the Bridges family lived on one of the McCoy farms south of Ozark. Possibly our father figured that with four sons growing up he needed a patch of timber to give them employment. At any rate that turned out to be our future occupation, for Father eventually set up a saw mill operation. We lived three years as tenants on the Captain Anthony Arnold farm on Bull Creek, then Father paid $600 for a 200-acre tract adjoining, and we had the first land that we could call our own. From a neighbor Father bought a vacant log cabin which was taken down log by log and set up on our place. The logs were of pine cut from the nearby "pinery" on Pine Ridge and hewn to 16 inch width and 6 inch thickness. To supplement the big 18 X 20 foot room Father built a timber leanto on the rear, which he divided into two rooms, the kitchen and a bedroom. Also, an important feature in a home where warm weather extended over half the year, a porch spread its shelter over the entire front. The roof covering it all was made of handriven "shakes" and the floor was of six-inch pine boards. Set on a high point of bench land at the mouth of Turkey Holler, the cabin and its porch provided a pleasant view and a serene spot for visiting, or for Mother while she shelled peas for dinner, rocked the baby, or did the family sewing. Our only sister, Bessie, (later a, teacher and wife of Frank Anderson of Ozark, but who died in December 1959) was born here early in January 1909. Two log barns, each with two leanto sheds and a smokehouse, also of logs, completed our farmstead. We did not need a well, for a clear spring emerged under the hill some thirty yards northeast of the cabin.

Down creek a quarter mile, on Bluff Point overlooking the stream, stood Glendale School. Here I took eighth grade or "Fifth Reader" work, and here I came under the benign influence of two teachers who decided my life's work.

Someone once described a liberal education as Mark Hopkins on one end of log and a student on the other end. I did not have the great educator as a mentor, but I did have in Tom Mapes and the Reverend Arthur Wilson two of the best possible substitutes. I suppose nothing is as important in the uncertain, hesitant lives of adolescent boys and girls as the encouragement of adults, especially understanding teachers, who see possibilities for growth in the awkward developing personalities of such youngsters and provide a stimulus to their dreams and talents.

[10]

Both Mr. Mapes and the Reverend Wilson were warm, outgoing types. Mr. Mapes was elected county commissioner of education after my one year under his tutelage, and his place was taken by Arthur Wilson for the two years in which I reviewed the work of seventh and eighth grades. Both men supplemented for me the regular work of the grades by extra-time instruction in the high school subjects of rhetoric, algebra, and physical geography. They supplied me with books otherwise unobtainable, and willingly came to my home on occasion for the additional instruction I needed. It was customary in country schools for the overworked teacher to ask his senior pupils to hear recitations of lower graders while he concentrated on the advanced classes. Thus I and two of my classmates became assistant teachers. Mr. Mapes complimented us by saying that he wanted all three of us to become professional teachers, since we had the ability and the "touch". Two of us did; the other became a high official in the Civil Service at the nation's capital. I was later to use this method in my own rural schools to care for the 40-odd pupils usually registered, ranging in age from five to twenty years.

Thereafter for several years I helped Father in the timber and on the farm. Although railroad ties and stave timber had been going to market at an accelerating rate since the railhead had reached Chadwick in 1883, the supply and the demand seemed endless. We can look back now and see that timber-cutting reached its peak about 1909 and thereafter declined as the forests thinned out. In my teen years, however, we saw few signs of this. White, red and black oak crowded the view everywhere one looked. Only the best white oak was cut for ties and staves. Red and black oak made first-class shakes and rough lumber.

A husky woodcutter could fell, trim, and work up about ten ties in a 10-hour day, using only hand-operated axe, saw, and broadaxe. It was back-breaking work; and most hill people fell back on it only when cash money was needed for necessities which had to be bought at the store, such as sugar, salt, and cotton goods. A steam-engine-driven sawmill, on the other hand, could enormously increase production. Father set up one of the first of these in the Bull Creek region. We thus used the timber growing on our own place, then branched out to buy tracts of standing timber from neighbors, and to doing custom sawing for neighbors who hauled in logs. This provided winter occupations for the entire family for several years. It was supplemented in summer by a movable threshing rig Father bought and put on the road. We moved from one farm to another throughout the eastern end of Christian County as the crops of oats, wheat, and barley ripened. It was my job to care for the steam engine; and I can still close my eyes and see that endlessly moving belt between engine flywheel and the separator some fifty feet ahead, and hear the steady chug of the wood-fired engine, and smell the pleasant odor of hot oil mixed with steam. We also had our own chuck wagon along, and my wife and Charley's wife prepared our simple fare.

In spite of Mr. Mapes compliment on my ability. it was not my intention at first to become a teacher. Like many another isolated farm youth, I was in love with railroading. To us no figure was as manfully romantic as the cool engineer of a crack passenger train, sitting imperiously in his cab, one gloved hand on the throttle, the other perhaps raised in greeting to a fellow railroader on the station platform.

Meanwhile, I had acquired a horse and buggy, and a girl. She was May Bilyeu, daughter of George W. "Bud" Bilyeu and his wife Emma. Her folks lived in the Prospect community south of Ozark. One of the places young people could meet were the monthly preachings held at various schoolhouses, used also as meeting places. I met May at such a meeting at Victory, near Christian Center; and before long we were attending meetings and pie suppers and play parties together. We were married November 20, 1915. We bought a 40 lying next to my parents' land and on this in 1916, using lumber from our family sawmill, I erected a three-room house, two rooms down and one above. I also built a large barn with some assists from my family and neighbors. Here the first of our three children, Clifton, was born, only to pass away tragically at the tender age of four and leave us bereft. Two daughters, Iola and Ruby Lee, both of whom became elementary teachers, came later. Each has given us a grandchild: Judith Elaine Glover and Peggy Jean Melton.

In 1917 my neighborhood school, Glendale, found themselves facing a school year without a teacher. The directors, consulting with the county commissioner of education, my old teacher, friend and mentor, Tom Mapes, were told that I was well qualified and had only to pass a simple examination to receive a third-class teaching certificate. The directors came to see me, offered the school, I took and passed the examination, and the die was cast. I was to be paid $40 a month for a term of six months. In addition, for doing my own janitor work, I would be paid an extra $1 a month in the warm months and $2 whenever the heating stove had to be fired.

Since I now had a family the extra money was welcome. It would supplement my work on the farm in caring for the cattle, horses, pigs and Sheep; and I could still help Father on sawmill and threshing rig as time warranted.

[11]

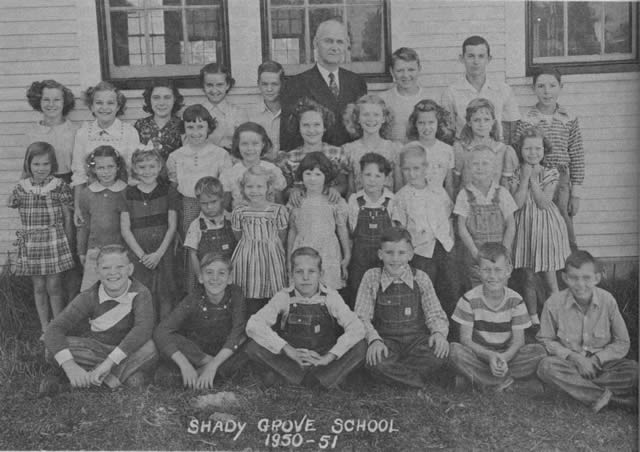

Mr. Bridges stands here in the back row of his pupils at Shady Grove School, three miles southwest of Sparta, Mo. After the year 1950-51, the school was closed and the pupils transported to the consolidated school in Sparta. Percy Bridges taught at this school seven terms.

My day began early, about four in the morning, when I arose and did my farm chores by lantern light. After a full day, sitting by coal oil lamp light at the kitchen table, I corrected the pupils' written work and pored over high school subjects I was taking by correspondence from the American School of Chicago. Eventually, when State law required all teachers to have high school training, I had my diploma. In later years I took courses at Drury College and Southwest Missouri State in Springfield so that I might continue to teach in the centralized school, which resulted from consolidation and replaced all country schools of the Glendale type.

In the twenty years before reorganization was completed I taught the eight elementary grades at Glendale, Oakwood, Tillman, Enterprise, Liberty, Fairview, and Shady Grove. My last fifteen years in the profession were spent chiefly at Sparta, with the final two at Chadwick. It was my good fortune in these later years to be assigned the fifth grade. These boys and girls aged 10-11 are in my opinion the prize all dedicated teachers hoped for. They are eager and they are coming out of their chrysalis of the early acted-upon years to be active individuals in their own right. They are learning to be civil and are curious to know; yet they have not as yet been transformed into the awkward, uncertain personalities they will perforce become when their sex has made its demands felt.

Although I have accumulated neither riches nor honors as a teacher I have no regrets. I have kept close to my roots in the soil and rocks and friendly people of my native hills, and have perhaps touched the inner core that all boys and girls have for good. I did not have to share that experience common to so many in our day: of going off among strangers to make my way, only to return in my age and find my people strangers. In some small ways, particularly in the upright and useful lives of my former students, I can see a reflection of my influence. It is a sufficient reward.

[12]

This volume: Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues

Other Volumes | Keyword Search | White River Valley Quarterly Home | Local History Home

Copyright © White River Valley Historical Quarterly