|

Volume I, No. 1, Fall 1973 |

The Last Day of School

from the unpublished manuscript,

We were late when we arrived at the school house for the last day of school in early April. I opened the door near the front of the room and half pushed Danny in before me. I carried the basket of dinner; Pete carried the baby, Jane. The school children and their parents turned to watch us as we walked awkwardly to the rear in search of a seat. I set our dinner on a table already loaded with baskets and covered boxes.

By the time we reached the back of the building; we had ceased to be the center of interest and everyone had gone back to listening to the teacher, who was giving geography questions to the whole group in quiz form.

I took Jane, and Pete, who spied a seat next to Randy, tried to persuade Danny to sit by him. He wouldn't stay, but followed me around the room to an empty desk in front. I was skinny enough to squeeze into one of the little desk chairs which are usually left for late comers. I set Jane on the slanted desk top, settled Danny beside me on the seat and listened to what was going on as I removed their wraps.

"What's the capital of Alabama?" the teacher asked.

"Birmingham," a man shouted.

"Montgomery," one of the school kids coiled out just a second later. At the correct answer, the teacher put another chalk mark on the board under Side I. I realized I was on Side II, which at the time was several points behind the other.

[56]

Trying not to be too conspicuous, I turned slightly around to see who was there o Some day, I promised myself, I would get to a school doings early so I could watch other people enter. I saw the Carsons, Alexanders, Morgans, Chamberlains, McLains and most of the other patrons of the district. The parents and grandparents of the school children were all present for the children's most important day of the year.

"What is the leading farm product in Missouri?"

"Where are the three Forks of the Missouri River located.'?"

The teacher asked one question after another, My side caught up and finally won. As one side, then the other would get a point or two ahead, the excitement in the room would mount. Everyone tried to think of the answer. Often it was almost impossible to tell which side yelled the answer first. As she dismissed the school for morning recess, the teacher told us that we would cipher after recess until noon.

Rhoda Carson came to take Denny outside. He wasn't sure he wanted to go until she told him he could play on the sliding board. Rhoda, who loved to race and yell with Danny at hornet was quite a lady now; she had just passed the first grade.

After the children and most of the men went to the ball field, the women visited. The seventh and eighth grade girls, dressed up in their new dresses made especially for the day, refrained From joining the boys in the ball game. Suddenly grown up, they listened to the talk of the women.

"I'm glad Sammy graduates here where Randy and I did," Mary Carson said. "And I'm glad Rhoda got her start here."

"We won't have any more days like this now the school districts have all consolidated," Zorie complained.

"No, we sure won't. Closing up this school and bussing the children to school in town will take a lot out of the community," Stella Morgan agreed.

"I suppose the children will have some advantages there they can't get here at Oak -springs," Cora Alexander conceded.

"Undoubtedly, they will gain some," I said. "They'll have better teachers and better equipment, but they will lose something by being sent to town, too. Here the school is important to all of us even if our children are too young, or grown up, or if we haven't any children at all."

"Yes," Cora admitted. "I'd never go to town to school affairs like I do here. I'd feel out-of-place there because I haven't any children, but here I never miss a PTA meeting or school program."

"I do wish Danny could have started here," I said. I traced my finger over a large P.M. carved on a desk top by Pete years ago.

After recess, the teacher wrote everyone's name on the blackboard in two different columns, from the smallest children to adults. The best at ciphering were at the heads of the lists. I wasn't quite sure what a ciphering match was like, though Pete had talked about having them when he went to school. I noticed my name was near the top of the list. I knew it should have been much nearer the bottom as I couldn't add a row of figures the same twice. I expected many to withdraw their names from the list, as in almost any game some will not participate, but only one elderly lady withdrew. Everyone else took part, down to a Few pre-schoolers.

The teacher held the book of problems and answers. A little girl from each side started the match. The girls wanted to make marks. Making marks gives the little folks a chance to stay in the match. Within a certain time limit, the child that draws the most chalk marks on the board is the winner of the round. Our side won the first round, the girl from the other won the next, but we won the third time, giving us two out of three trials. The defeated child sat down. Her name was erased from the bottom of the list and the next one marched to the board. The newcomer always has first choice of kind of arithmetic, then the contestants take turns choosing. As we progressed up the lists of names, addition, subtraction, multiplication and. division were called for, but the favorite of most was addition. Some of the best at ciphering requested cancellation and fractions. Frequently one would hold his place at the board to turn down several opponents. Billy Chamberlain, now a tall eighth grade student, turned down all the remaining children on the other team. He called for subtraction and usually had the remainder ready when the teacher finished reading the problem.

[57]

Beside working the problem correctly, the contestant must read the answer before he wins. Some would be knocked out by putting the comma in the wrong place in their hurry, or not reading the answer correctly even though they had figured right.

As long as the school children lasted, Billy stood his place. Though not as good in addition, he usually won there, too. He turned down two men before someone called for long division. Billy looked worried; he sat down grinning when he was beaten.

Everyone was in good spirits. No one actually cared which side won. It was a way of having a good time, and everyone certainly was enjoying himself. People at their desks had paper and pencils and worked the problems as they were given out to those at the board. When a contestant got the wrong answer the crowd usually let him know it before the teacher had located the right one in the back of the book.

Pete and Randy, seated at a desk in the back, were having a private contest to see which could get the correct answer first. They had collected quite a group around their desk as their jests and laughter increased. Their game divided the attention of the room and frustrated the teacher, used to calling down such disturbances. But she could hardly call down the president and clerk of the school board for not paying attention.

The diversion was broken up when Randy was called to the blackboard. The problems became more complicated as the match progressed. From single addition given to the children, the problems now had progressed to four columns with as many as twelve lines to add. Interest increased measurably when the older contestants got to the board. They wrote down the numbers more quickly than the teacher could call them out even though she read rapidly. After she gave the second line, the contestants would jot one, and sometimes two, numbers beside it. As each succeeding line was written down, more numbers were scribbled beside the figure. When the teacher called "Add," the first column and sometimes the second were already totaled.' Then seemingly as quickly as the contestants could lift their hands up the row of figures, the sum was ready and they yelled out the answer.

They wasted no time. When division, subtraction or multiplication was called, they drew the lines before the problem was given, ready to start figuring immediately. I watched enthralled; this was better than a free movie.

When Rex Morgan's name came up, his wife was at the board grinning confidently. Rex was good at addition from his long practice at the store, but Stella was better.

[58]

"Can I cipher in lumber measurements?" he asked. Stella's confidence disappeared.

"Yeah, let 'em," Shorty McLain shouted.

"I'm afraid lumber measurements aren't included in a ciphering match," the teacher said.

"Should be," Rex grumbled. "I'll take addition."

The couple worked three problems before anyone could tell which one yelled the answer first. Then the teacher decided Stella got it. After several more problems, Stella was declared the winner but from my seat I thought Rex got the answers as quickly.

"Rex first met Stella at a ciphering match," whispered Cora Alexander, who knew everything worth knowing about her neighbors. "He was the champion of Oaksprings years ago when we ciphered against Happy Hollow School. Rex could hardly stand it that she turned him down. He still tries to outdo her, but seldom wins."

When Rex sat down, Dave Chamberlain's name was called. I expected to see Stella turn him down quickly, as he had never gone past the sixth grade in school, but I was dumbfounded at his performance. He disengaged his long legs slowly from the desk and strode up to the board, smiling as he remembered something.

"Some time back," he drawled as he picked up a piece of chalk, "when I was just a shirttail of a boy, I turned down the whole school. I made marks faster'n anybody in school and I couldn't even count 'em." Ready now for business, he turned to the teacher:

"Give me multiplication, but I don't want nary a nine in it. I never could learn my nines."

As everyone expected the problem was full of nines: 9879 times 98. A howl went up in the room when the problem was read, but old Dave only grinned sheepishly and had the correct product before Stella had stopped laughing.

"Laws-a-mercy," Zorie exclaimed, "Don't you'uns remember that old trick of his?"

"Addition," Stella requested, suddenly sobered. The problem was the longest one yet given, but Dave again had the answer faster than I'd have thought he could write it down.

"It's been many a wet and dry day since I used to cipher," Dave beamed, "but I can still stand up agin you young'uns." Dave was having him quite a time.

He turned down several before he met his match; he last in addition.

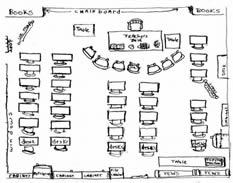

Typical plan for a modern one-room school

[59]

"You'd best made marks, Dave," someone taunted him.

Then it was my turn at the board. I called For long division. That seemed to be the least popular, and since my opponent had won in addition I hoped she wouldn't be so quick in division.

"4-9-8-4-2 divided by 3-5-1," the teacher gave out.

I had Forgotten to draw the lines For division and wasted precious time getting the problem written. If there were any short cuts in division, I couldn't remember them as I began to Figure. "One": I found the First digit easily and was debating whether a three or four would be

the next when my opponent called: "One hundred Forty-two." "That's right," the teacher said.

My opponent asked For addition next. I had never found it difficult to think in Front of people when I'd done impromptu speaking, but I found that trying to figure with seventy people watching made me as embarrassed as if I were changing my clothes in public. I got completely rattled and knew stage fright For the First time. Yet I had just watched people who ciphered with ease but wouldn't stand up and talk before the same group. I looked at the long column of figures I'd written down and began to add. I realized somewhere my education was neglected. I had always believed it so superior.

"Six and seven are...eleven, no." I started up again more slowly. "Six and seven are thirteen, and eight are...Thirteen and eight are..." If my life had depended on it I couldn't have thought what thirteen and eight totaled. So I started at the top of the column intending to add down it, when my opponent read the correct answer. I humbly sought my seat and busied myself with comforting Jane, who didn't approve of my dumping her in Cora's lap so abruptly.

I had some satisfaction when the woman who had turned down Dave and me turned down the rest of our side. While we women set out the dinner we'd brought, I decided that the next time I was caught in a ciphering match I'd have to pinch Jane to make her cry or take Danny to the toilet when my turn came.

I used to love basket dinners. That was one occasion when I could eat all the fried chicken, cake and pie I wanted. But after the children had arrived I didn't fare so well at public dinners. Today, by the time I filled a plate For Danny, got him settled by Pete, then went back to Fix a plate of things year-old Jane could eat, fed her, got extra pieces of cake For Danny and innumerable glasses of water for both children and tried to mop up the water with my handkerchief that Jane spilled, everyone else had Finished eating. I had made so many return trips to the table filling the children's demands that I was ashamed to fill another plate For myself, so I ate what Jane left and wondered how I'd ever 'clean up the mess she'd made with a piece of

chocolate cake in the spilled water. The teacher gave me some damp paper towels, with which I made a pass at washing Jane's hands and face. I brushed the mess from the desk top and let that on the floor wait For the teacher to sweep out the school for the last time.

The children's program in the afternoon seemed to all of us to be exceptionally good. We laughed at little Jody Morgan as a doctor diagnosing the symptoms Of big Sammy Carson, and we all felt proud of Susie McLaln as she sang a solo in her beautiful voice, with the other children joining in the chorus.

[60]

Sammy read the last will and testament of the five eighth grade graduates after they had received their diplomas.

"And we leave Oaksprings school to go to high school. We won't forget this school. For not only we graduates but none of the lower grade students will come back here to school. As our last wish, we hope that the ones who come after us will like their teachers and school in town as well as we've liked Oaksprings school and our teacher here."

The teacher daubed at her eyes with her handkerchief as she rose. She thanked the school board and the patrons for helping and cooperating with her. She said she would miss the boys and girls when school started next fall but she was sure they would appreciate their advantages at a larger school. After she had given each student his report card and a candy bar, she dismissed school, but no one moved.

Presently Stella Morgan said that she was more than pleased with the way Jody had learned this year. Randy commented that his children seemed to get a lot out of school this term. Every parent present had a favorable remark to make. As parent after parent expressed satisfaction, the teacher's tears came in earnest. She merely nodded her appreciation or said, "I'm so glad."

Mary fumbled in her purse for her handkerchief, I heard Cora sniff beside me and I was very busy myself fooling with the hem of Jane's dress. The school children, still seated together on the platform, looked miserable. The boys reached in their pockets and didn't dare look up. Rhoda broke from her chair and ran sobbing to the teacher, who held her close. Several more of the smaller children gathered around.

As the moment became unbearable Dave said, "Let's all give the teacher and young'uns a good hand." Amid the loud applause we regained our composure. When we left, we locked the door of the outmoded one-room schoolhouse for the very last time.

[61]

Copyright © 1981 BITTERSWEET, INC.

Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues