Volume 2, Number 5 - Fall 1965

The Ozark Bluff Dwellers

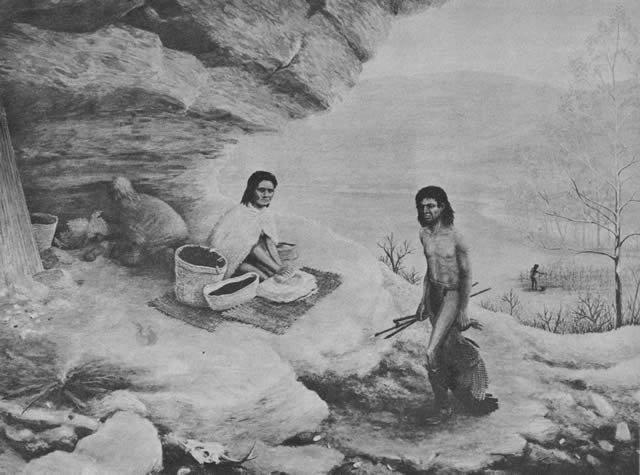

A Painting

by Steve Miller, the Artist

That good science and good art combine in painting a prehistoric subject appealed to me as a top challenge in the Arts. The necessary ingredients in this absorbing and exciting pursuit include patience in research, artistic battle strategy, and small amounts of the right kind of paint.

I chose the subject "Ozarks Bluff Dwellers" as the first in a series of area documentary paintings. Then began the research. At the museum of the University of Arkansas I sketched materials salvaged from White River Bluff shelters. Field archeologists from the University of Arkansas and from the University of Missouri freely gave advice which aided in establishing a picture of a typical shelter, its inhabitants, and the way they lived. I chose subject matter for the painting which was above question in the pronouncement of most authorities. The "Ozark Bluff Dwellers" by Mark Harrington, published by the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation of New York, proved a valuable research volume.

I set up my easel in the Ralph Foster Museum at The School of the Ozarks. I soon saw interesting side benefits occurring as the work on "The Ozark Bluff Dwellers" progressed. Right away the many visitors to the museum and studio showed interest in the project. Arguments, suggestions, and comments came forth in a kind of "cultural buzz" from Boy Scouts, from expert anthropologists, and from many others. I also used the project as a progressive demonstration in my art classes as it involved a very real application of principles of composition and color in a subject of regional interest.

Prehistoric Bluff Dwellers of the White River Valley, Ozarks Plateau.

-Painting by Steve Miller, on display in Ralph Foster Museum, The School of the Ozarks

[16]

I made preliminary sketches, contemplating the possible addition of elements which might come to my attention after getting the painting underway. For this reason I used the principle of "radiation" in the composition. The radial principle employs a series of rhythmic lines radiating from a point in the picture. You will locate this point between and back of the two women. The basic structure of strong lines served as a device upon which all elements were arranged and insured a unified composition.

The support for the painting was a piece of one-quarter inch fiberboard coated with six thin layers of polymer gesso. I chose permanent acrylic polymer paints for the picture as they can be handled in a thick or thin manner. They dry rapidly and are useful in the rendering of fine detail.

To this support I transferred the penciled sketch as perfected. The color note of the painting is complimentary, (opposite on the color wheel), consisting of the purple of the Indian maize near the center of interest, surrounded by predominately yellowish tones.

Many problems arose during the painting, which portrays a scene of 1500 years ago (give or take a few hundred years). The time determined the character and coloring of the vegetation. I was surprised to learn that the Indian maize, cultivated by the early agriculturists in the White River Valley, had stalks similar to the short-stalked kaffir corn, with small ears found only at the top of the stalk! Corn cobs and kernels have been uncovered in several of the shelters of the area. The ‘nubbins’ sometimes seen today growing among the tassels are throw-backs to the early maize.

Painting the wild turkey proved a bit of a problem. The prints of the noted authority, Audubon, were questioned since there arose the possibility that they did not go far enough back into time to accurately reflect the bird of 1500 years ago. At this crucial and vexing point, an authority, A. R. Mottesheard, Conservationist at The School of the Ozarks, entered the studio. He became interested in the turkey problem and also supplied valuable information on the subject of ancient maize.

The well-preserved pieces of basketry, weapons and clothing at the University of Arkansas made accurate painting a pleasure. Some of these articles were found well preserved in the dry shelters, even to clothing and seeds. Many archaeologists believe that the seeds from the giant rag weeds and sunflowers were ground into flour. Both Ray Wood and Dick Marshal of the University of Missouri, when approached separately, while the painting was in the idea stage, came up with exactly the same answers to my question about the hunter. They said to show him bringing in a wild turkey or deer. Then I knew that both of these eminent archaeologists had dug out many bushels of turkey bones from Ozark shelters.

Credit must be given to Miss Joy Patterson for her assistance in locating background material; to Miss Mary Anna Fain and Dr. Alice Nightingale for finding many books; to L. S. Reid for valuable suggestions; and to Tom Millard of Harrison, Arkansas, for showing me where bluff dwellers usually built their fires; to many enthusiastic students who helped in innumerable ways; and to the many welcomed studio visitors.

The recognition and naming of the "Ozark Bluff-Dwellers Culture" was first attributed to Mark Harrington, a representative of The Museum of The American Indian, Heye Foundation,. New York. In the early twenties Mr. Harrington, with a crew from the museum, and often assisted by local residents, conducted a series of trial explorations in the Ozarks. He subsequently centered most of his activity in Benton and Carroll Counties of Northwest Arkansas, where several dry shelters were found with the aid of native guides. Materials salvaged from these shelters, especially the Bushwhack site, were in a good state of preservation.

Later archaeological work was accomplished in the general Bluff dweller area of northwest Arkansas, northeast Oklahoma, and southwest Missouri by field crews from the State Universities. Amateur archaeologists have also worked in the area. A note of urgency was injected into the archaeological picture when plans were announced for the building of Table Rock Dam, which would put valuable Sites under water forever. Quick action preceding the sequential construction of the big dams resulted in significant salvage operations by the University of Missouri in the Table Rock basin; and by the University of Arkansas to the south.

Archaeological investigations have shown that the combination of dart and atlatl (throwing stick) was definitely the weapon of the bluff dweller. In addition to the atlatl and dart, which have been proven in recent tests to be formidable in taking large and small game, the bluff dweller’s state of cultural progress is bolstered by the evidence of his agricultural ability. His knowledge of the preservation and cultivation of plants such as maize, giant ragweed, sunflower, and many others, is unquestioned. The seeds have been found, well preserved, in the shelters. He was also an expert weaver of baskets, mats and nets. Many of these artifacts, together with a few well-preserved articles of clothing such as moccasins, sandals,

[17]

breechclouts, and feather robe fragments, have been salvaged from dry shelters in Benton, County, Arkansas.

The typical bluff dweller in the White River valley lived in a shelter which usually faced any direction but north and his habit of having his waste material out of the front of the shelter or simply leaving it on the floor, has provided one of the most valuable sources of material for the benefit of archaeologists. The bluff dweller dug his storage pits for seeds and foodstuffs along the back edge of the shelter, with burials often nearby.

A great amount of work remains to be done to solve some of the mysteries of the prehistoric Ozarks. The bluff dweller culture is not the only ancient culture in the area; but at the moment is the best known, and perhaps the most colorful due to the perishable items found well preserved in the unique dry shelters.

Fascinating clues keep coming to light, pointing to the possibility of many other interesting cultures, some dating back past 10,000 years! However, the further one goes back in time, less evidence is available for the archaeologist. Time takes it’s toll. It is certain that the ancient cultures of the Ozarks area are some of the most interesting found in the Americas . . . always providing rewarding subject matter for painting Ozarks prehistory.

(Steve Miller is Artist in Residence and Curator of the Ralph Foster Museum at The School of the Ozarks. He not only puts colors in beautiful arrangements on paper and board, but oft times tells a story with those colors. He teaches not only students of the college, but he assists adults of the area who think they want to paint and who sometimes do. At the Annual Fall Meeting held October 2, Mr. Miller told the story of his painting, "The Ozark Bluff Dweller." JRM)

[18]

This volume: Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues

Other Volumes | Keyword Search | White River Valley Quarterly Home | Local History Home

Copyright © White River Valley Historical Quarterly