Volume 37, Number 1 Summer 1997

Floyd Jones' Memoir

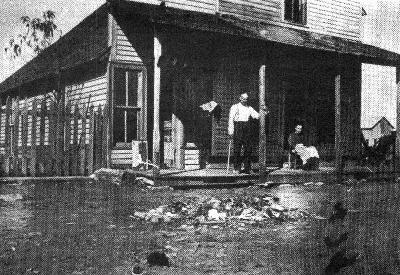

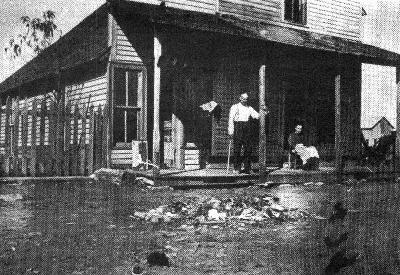

At the Taneyville Hotel. Thomas Osborne (1857-1926)

and Susan Elizabeth Osborne (1838-1926), Thomas' mother.

At the Taneyville Hotel. Thomas Osborne (1857-1926) and Susan Elizabeth Osborne (1838-1926), Thomas' mother.

I am writing [this] book at the request of my children with the

thought in mind that some of them will be living at the end of the centuary

and will want to bring it up to date then. There has ben much said and written

about this country, I want to get the record straight. I lived here over a half

centuary I am writing it as I lived it from memories that are still as when

it happened. There is much to write about [and] I have tried to select items

that will be of most interest. I have witnessed the advent of the kerosene lamp,

matches, the ox team replaced with the horse, the horse and buggy days replaced

by the motor age, and the areoplans is traveling faster than sound, and the

space age is expected to be born at any time, so what are you people that expect

to live to the end of the centuary expecting to see? It looks like it has all

happened in the first half of the centu ary. I dedicate this history to my children

and grandchildren, hoping it will be of interest to them as they look ahead

to more great events.

The families that made up our neighborhood

Bob Cantrel

Gibs May

Rat Vining

Jack Vining

Mr. Fronebarger

Bill Fronebarger

Sid Fronebarger

W W Walden

Fullertons

Uncle James Cox

Nute Cox

Hardy Cox

Bill Cox

Mr. Garber the post master

Wash Berry

Bill Berry

Bill Hall

Bob Lewallen

John Boswell

Henry Berry

Main Berry

Clem Hawkins

Andrew Hawkins

Jim Stockstell

Dr. Irwin

Bill Irwin

Uncle Bill Hawkins

Bill Mattox

[13]

Joe GarberIsaacs

JKRoss

Truman S powell

Bill Powell

Bill Hulsey

albert Hulsey

Mr. weire

Hardy Goodall

omer Goodall

Elmer Goodall

Tom Compton

Dr Compton

Mart Compton

Nute Compton

Bill Crowder

Mrs. Logan

Ben Logan

Lum Logan

Jim Miles

Emanuel Miles

Root Barker

Jack Shephard

E B wright

uncle Starling mattox

Tom Berry

Jim Mattox

uncle Zeb stockstill

The Fausetts

uncle Bob patterson

uncle Dave Hillhouse

uncle Bill Hillhouse

oss stockstill

Billie Stockstill

aunt Mary Stockstill

the Clinkenbeards

shurman Bull

uncle Lum Hawkins

uncle shepphard Jones

Calvin Jones

Martin Jones

George Gregg

uncle Dan Gregg

Tom Jones

The seigis Kirkendalls

Jess Stockstill

Tom stockstill

Taney County 1886 to 1903

my father M W Jones moved from Oregon County [Mo.] to Taney County about 1880 with his mother and three sisters. His mother home steaded eighty acres on Roark Creek four miles north west of Branson. They built a log house, started clearing land and farming. Enos S. Isaacs, my mothers father and family came from Cass county [Mo.] about the same time. He home steaded one hundred and twen ty acres just north of Dewey Bald, built a log house and started farming. Father home steaded eighty acres joining his mothers eighty on the west and cor nering grand father Isaacs one hundred and twenty He built a log house. He and mother were married march 1884 and started clearing land, making rails to fence it and started raising a family. I was the sec ond child [with] one sister two years older than me. There were nine of us born in the old log house, and what I am going to write about our way of life then may be hard for some people to believe but it is all true. It all seems like yesterday to me.

Our neighborhood was from the forke of Roark Creek at Garber down Roark and Fall Creeks to white River. These are the families that comprised our neighborhood at that time: uncle Gibbs, may and uncle Rat Vining on the west prong of Roark, Mr Walden and uncle Jack Vining on the east prong of the creek, the Fronebargers at the forks of the creek. Down the creek were uncle James Cox, Hardie Cox, John Wess Brite, Kirkendalls, my father, uncle shep pard Jones, aunt Mary stockstill, uncle Zeb Stockstill and Jim Mattox. On the west side of Roark the Cantwels, Garbers, Nute Cox, Isaacs, W R Cox, Truman S Powl, Bill Powl, J K Ross (old mat), Calvin Jones, Martin Jones, Tom Jones, Uncle Jerry Cochran, Dean Cox, uncle John Boswell, uncle Bob Lewallen, Bob Jones, the Fausetts, Ruf Barker, the Mileses, Jack Shepphard, Dr Compton, Mort Compton, nute Compton, Tom compton, uncle wash Berry, Bill woods, Mrs Logan, E B Wright, mr weis, van stevans, bill berry, Ben Logan, Lum Logan, Dr Irwin, Bill Irwin, W H Crowder, Henry Berry, James Stockstill, uncle bill Hawkins, Tom Berry, Bill Mattox, Main Berry, uncle Starling Mattox. On the east side of Roark the Frost, the Fulertons, John Larue, Bill Combs, Tom stockstill, the Doolins, uncle Lum Hawkins, the Clinkenbeards, the Sherman Bulls, uncle Dave Hillhouse, Joe Garber.

All this teritory was divided into two school dis tricts. The Branson district came up the creek to about one mile below Gretna and the old Roark dis trict extended up the creek along the Stone [and] Taney county line north out past the seventy and sixty five highway Junction. The Roark school house was located about half way between Gretna and Garber. All the children had to walk to school, some a distance of three or four miles.

All these people were neighbors all making their liveng the same way, digging it out of the poor rocky ground. They grew nothing for market but cotton and live stock. They always tried to raise enough corn and wheat for bread and to feed the horses, and fatten the hogs for meat and lard. The hogs were fat tened on acorns first and then fed corn for a while to harden the meat. Cattle and horses were on the out sid [open] range. This was a most beautiful grazing county then; open timber and tall blue stem grass [with] no brush.

Our house was one mile east of Dewey Bald. Grand father Isaacs gave mother forty acres corner ing fathers eighty on the north west and when Grand mother Jones died father bought her eighty on Roark, making us two hundred acres. We all lived in one room: cooked, eat, slept in the same roam. No cook stove, no lamps; mother did all the cooking on

[14]

the fire place with iron pots and [a] skillet and lid. We tried to eat supper before dark. Some times Mother would twist a rag string, lay it in a tin plate and put lard on the string to make a grease lamp. Father would read the bible by the light of the fire place.

We had two big home made beds and a trunnel [trundle] bed that rooled [rolled] under one of the large ones in day time. Mother had a spinning wheel. She carded and spun cotton and wool yarn and knit ted all our stockings and gloves. She made all our clothes by hand. We had a smoke house where we stored our meat and lard, a barrel of sauer kraut, a barrel of sorghum and a barrel of pickles. We stored potatoes, apples and cabbage and turnips in the ground.

We had an ash hopper, made by splitting a hol low log [and] using one half for a trough, sitting four forks in the ground, poles laid in the forks to support two foot clapboard, one end in the trough. We saved all the ashes from the fire place in the ash hopper to mak lye for soap making in the spring. All the of falls [offals] from butchering were saved for soap grease. In the spring was soap making time. The ashes were socked [soaked] with water until they were thourly wet and the lye would start to run out of the trough. The lye was poured into a large kettle in the yard till it was full. It was boiled and greas added as long as the lye would eat it. It was tested by dipping a feath er in the lye. If it stripped the feather it needed more grease. The soap was soft and was stored in kegs. Besides being used to wash dishes and clothes, it was also used to grease wagons. Mother did the washing on a wash board. She would place a dirty garment on the board, dip her hand in the soap, spread it on the garment and rub it on the board. Then the clothes were placed in the big kettle, boiled, then rubbed on the board then rinsed, handed [hung] on the fince and brushes to dry, then sad irons were placed on some coals in front of the fire place to heat for the ironing. It took about all day to do a large washing.

We had a rough board floor in our house. The over hed joists were logs, board laid on them. We called the atic a loft. The roof was clapboards two feet long. They turned the rain very well but a blowing snow would sift through and settle on the beds. We were as happy a lot as you ever see on cold winter night [with] a big fire in the fire place, the children playing, mother carding cotton or wool, making rools to be spun into yarn, or maby she would be running the spinning wheel or sitting by the fire knitting, sewing on a new shirt or pair of pants, father read ing the Bible by the light of the fire place. He would have the children throw some dry wood on the fire to mak a better light. When it was real cold you had to turn first one side and then the other to the fire to keep warm.

People

visited a lot. A family would go to a neighbors and visit on long winter nights.

Then there was a rough house all joined into one room, the children playing

games, the old folks sitting around the fire talking, maby the women working

at something. When the kids began to get tired and sleepy they would come up

around the fire and listen to the old folks tell tall tales, some of which were

so scary I would be afraid to go home in the dark. We had no matches, hat [had]

to keep fire all the time. If our fire went out some one had to go to a neighbors

and get a shovel of fire.

I have saw father load his old rifle with powder and cotton, fire it against the wall, pick up the cotton and kindle a fire with it. We dident can vegetables, we caned [canned] fruit in stone wear jars, sealing it with sealing wax. We dried peaches, apples and pumpkin. There was always a tall cedar churn sit ting by the fire place with milk and cream getting ready to churn. We had plenty to eat, soda butter milk biscuits1 or corn bread, plenty of vegetables, ham and sorrel gravy, bacon or sausage, country but ter, wild turkey and venison. We got it from the smoke house instead of going to the store. All we bought at the store was sugar, green coffee, shirting calico, blue dinham [denim], a three hundred pound barrel of salt onc a year for salting the stock and cur ing the meat, lead, shot, powder and gun caps for the old muzzle loading guns. We also bought plow points, horse shoes, wagon tires, chains and hames for har ness.

We all worked and I mean worked from sun up to sun down. Each winter we cleared some new

[15]

ground, made rails to fence it and cut our winters fire wood, deadening the trees that were left. Each spring we had to drag the dead trees togeather that had fallen into piles and burn them. We used a home made plow with a tounge [tongue] to plow new ground. When it stuck under a stump or root the team could help back it up and get it loose. Long roots would break and fly back and rack our shins [and] big rocks would fall back on our feet. It required a steady team and a patient man to plow new ground. Everything was planted by hand and cultivated with single stocks and double shovels. We cut hay with mowing scythes and raked it with homade wooden pitchforks. Hay and oats were har vested with cradles [and] threashed by horse power machine.

When I was large enough to carry a bucket of water I had to carry water to the harvest crews and turn the grind stone to sharpen the cradle blades. It seemed to me it took forever to grind one. The people helped each other through harvest and threashing. They called it swapping work. They would all get togeather and go from farm to farm harvesting the ripest fields first. The women did the same way with the cooking.

There was always plenty on the table and always a lunch in the field the middle of each morning and afternoon, and believe me they could drink lots of water, and I was always busy carrying watter from a spring, sometimes quite a long distance bare foot over the hard rock, briers and thorns. Late in the afternoon I had to go out on the range and bring the milk cow in for milking. I would ride a horse out on some high place and listen for the cowbell, and there were bells of all sizes and sounds over the woods. Many times I would go to the wrong bell, and have to do more riding. Sometimes they would be so far away I was afraid to go after them, for fear I might get lost.

Many a night when the sheep failed to come home I had to go out on top of Dewey Bald and drive them home. They would always lay down on some high place at dark and were hard to find. I would stand and listen for the bell to jingle, which wasent very often. I would go around on the other side, slip up and give them a scare. They would never stop runing till they were home.

I have been on top of Dewey Bald before daylight and could hear the wolves howling, the foxes bark ing, the quail whistling and wild turkeys gobbling, everything else quiet. As the sun began to rise I could hear the wagons bouncing over the rocks on Roark and fall Creeks as the farmers started to work, then I could hear uncle John Boswell down at the salt ground down on Fall Creek calling cattle, then you could hear the cow bell start ringing and see the cat tle begin to come down from every ridge and start down mutton hollow to the salt ground.

You could go there now and wouldent see or hear any of those things; possibly you would hear an auto mobile going over the highway that runs over the Bald or you might hear a train come out of the tun nel and on down the creek to Branson. Quite a dif ference time makes. You can go to the top of Dewey bald and the old post oak tree that stood alone is now surounded by other timber that has grown up since. It was all cut then; the old signal tree could be seen for miles in all directions. When we were working in the fields we had to work till sun down. On long hot summer days the sun went down in the top of the old tree and seamed to hang there and never go down. We always watched it pretty closely.

There wasnt many jobs. The wages were fifty cents per day, sun up to sun down, and dinner or thirteen dollars per month [plus] board and washing. A lot of times [it] was paid in bacon and lard. Mother helped in the field planting corn, hoeing and picking cotton. She would take a quilt to the field for the baby to lay on and the older children looked after the baby. Is there a woman living today that would do the work that my mother did? They would under the same sircumstances but thank goodness they dont have too.

Most children got one pair of shoes each year [although] some went bare foot all the year. The boys wore heavy boots. They were a problem to get off and on. We used a boot jack to pull them off. We used oppossum grease to keep them soft. We all went bare foot in summer. Our feet would get so hard we could run over the rocks. Our only trouble was briers, thorns and stone bruises. We generaly had a toe nail or two knocked off stubbing them aganst rocks.

We alway tried to get the crop layed by by the fourth of July, wheat harvest done. Every one went to the picnic independence day celebration. Every family loaded into the wagon with baskets of food and stayed all day. They had a limon ade stand, dancing platform, a swing powered by a horse [and] a speakers stand. They visited, danced and sang patarottaic [patriotic] songs, spread the lunch at noon and enjoyed it very much. After dinner some

[16]

one would read the declaration of independence and made [make] a few patraoctic remarks. Late in the after noon they loaded into the wagons and returned home. If we had as much as a quater [quarter] to spend that day we were happy

After the wheat was threashed we took a load of wheat to the mill, genearly to ozark or crane, some times to Reno or forsyth or to Moberlys mill on Bull Creek. We had enough flour for a year, and the bran and shorts for feed. Bill powell had a corn and saw mill at the head of Fall Creek. He ground meal on Saturdays. Many times when I was a small boy I rode a horse to mill with a sack of corn. I had to have the corn divided equaly in each end of the sack so it wouldent fall off the horse. I traveled the trail up the east side of dewey Bald, down the west side and down mutton hollow, which was then called the Hez Brite hollow, to Fall Creek, up the creek to the mill.

There was always a crowd at the mill; if you were late getting there you sometimes would have to stay all day to get your sack of meal as the sacks were placed in line as they came in and ground acording ly. The men visited, traded horses and pocket knives, [and] sometimes there would be a penny ante poker game out in the brush. They would spread a large handkerchief on the ground for a table and sit on the ground around it. Many times I would ride into a flock of wild turkeys along the trail.

We had about two to three months of school starting early in July and ending early in the fall so the kids could help gather in the corn and sow wheat, cut the cane and make the sorghum. We walked up the creek two miles to school; we had a good time along the way wading and playing in the creek pick ing papa [paw paws] and hasel nuts. There was a large attendance at the school. They taught to the tune of a hickory stick; the teacher kept a bunch of switches in the corner handy and no one ever got too big to take a whipping. We didnt have grades, just first, second, third, fourth and fifth readers. You was classed in the reader you were in. They taught spelling, arthmatic, grammar, phnialogy [physiology?] and geography.

I have a group picture of the school taken about 1899 when mamie prather was the teacher. She was married later to pres mankhy and was, as Mary Elizabeth Mankhey, [a] famous country news paper correspondent. H R awbery was one of our teachers when he was a young man. Teachers then received about thirty dollars per month and paid one dollar per week for board.

The school house was the meeting place for Church, Sunday School and various intertainment. We had no church buildings and no paid preachers. The people were mostly Baptist, Camelites [Campbellites] and Methodist. They were all very much anti Cthalic [Catholic.] We were taught that our forfathers came to this country to escape the per secutions of the Cathalic church, [as] there were no cthalics here. People were very sincear in their riligous beliefs, and held public debates on their differences which at times would become very bitter.

They held camp meetings in summer. They built a large brush harber near a good spring, and they came from miles around with the whole family and camped for a week. They would sing, shout and preach day and night. All had a wonderful time. They were having one of these meetings up on the bald by Kirbyville. (Captain) uncle Jim Vanzant and Mr pick et were preaching. Frank Campery, then a young man who was not too brite, came down from the meeting to lige vanzandts black smith shop. Lige was uncle Jims son; lige said to Frank how is the meeting going and Frank said "when I left there old Jim van zant was down on his allfours groanin like a horse with the bats, and old man picket was sitting there hauling [howling] like a tied dog." Any way the peo ple were very sincear about their belief.

When there was some one to be baptised and the creek was froze over they brok the ice and went ahead with the baptising, singing the old hymn "will the water be chilly when I am called to die." The preachers worked the same as every one else through the week and filled their regular appointments one Sunday each month at some school house or at some ones home.

We had no dentists. Several of the neighbors pulled teeth, and there was nothing to deden the pain. You just sat in a chair, held on to the wrungs on each side and tried to keep from hollowing; if you dident you were tough. On one occasion when I was small I went with dad to mill over to Moberlys mill on Bull Creek. He had a bad tooth ache when we got to the mill. Mr. Moberly told him to go to the house and Mrs Moberly would pull the tooth. I went to the house with him but stayed out in the yard. She made several attempts to pull the tooth but forsepts would slip off and he would yell. I was sure she was killing him. She finaly gave up the job. He was suffering ter ably by now.

[17]

It was late when we started home [and] it became dark before we got half way home. We were going down a steep hill through the timber. The rear wheel of the wagon struck a tree and there we were the rest of the night. When it became daylight he walked to mr Hopkins house about [a] mile away, got an ax, cut the tree and we went on home. The next day he went to dr Irwin and got the tooth pulled. He looked as if he had a weeks sickness.

This reminds me of a tale I have heard many times. A man was on his way to get a tooth pulled that was giving him terible pain. By the road side he heard a man yelling for the help; he stopped to see what was wrong with the man and discovered a tree had fallen on him and had him pined [pinned] under it. He looked at him and started on his way saying "the way you were yelling I thought you had the toothache."

Our health problems were bad. We had no screens and the flies were terable, had to keep them shoed off the table while we eat. Quite often one would fall into the food and some one would eat it and it would make them sick befour they could leave the table, and they were realy sick for a very short time then they could go back and eat. I have seen lit tle children sleeping just covered with flies all around their eyes and mouth. Some spred mzoqito [mosquito] netting over them to keep the flies off. Lots of young children died from summer complaint. The greatest killers amoung addults were pneumo nia, typhoid and malaria.

The doctors dident have much m[e]dicine and the patient had to war it out. It was just a battle to see which would Wm. The neighbors organized and wait ed on the sick. Pneumonia worked fast; you either died or recovered in a few days. Typhoid was a long hard battle for week. Most people had chills in sum mer. Some would chill every other day all summer long, and would be so thin when frost came they could hardly mak a shaddow. They worked, the chill would come on suddenly while they were at work. They would get [into] bed, pile on all the covers they could and nearly shake the bed down and their teeth would chatter. In an hour the chill would be gone and they would have a high tempiture. By the next day they would be able to go to work. The doctors gave them quinine and calomel and the store carried all kinds of pattent medicine and chill tonics but they kept on chilling til the weather got coal [cold] in the fall. Then they would fatten up and be OK till warm weather came agan in the spring.

People living in the White River bottom suffered far more from malaria and chills than those living on high ground. All the river bottom farm houses were on the bluffs for that reason. The doctors traveled on horse back caring [carrying] ther medicine with them, which was mostly calomel,2 quinine, castor oil and sweet spirits of niter to reduce fever. They also carried mustard plasters and other blisters. They had no stetiscopes to listen to your heart or fever themometer or nothing to test blood pressur. No one rarely had heart trouble and no one ever heard of high blood pressure; no one had appendicitis. Some probably died with to but it was called something else. There were no vccins [vaccines] only for small pox. There was no dyptheria. Children died with memberans [membranous] croup which might have been dyptheria.

No hospitals, no surgery excep amputations and lansing boils. This was done in the home; when a doc tor was needed some one rode a horse to Dr Comptons out at Table Rock, Dr Irwin at Branson or Dr Callen at garber. If the doctor wasen't at home and the case wasent to urging you left word for him to come; if it was serious you started riding to find him. There was no other communication but riding, no one rearly called a doctor for child bearth; the neighbor wemmen took care of that. Many women died with child bed fever. The older women were good baby doctors. They had many remidies, skunk oil for croup, onion tea which they made by wrapping a large onion in a wet cloth [and] roasting it in hot ashes in the fire place then squeezzing the juice out of it. They also made catnip tea, horehoun tea and many herbs and barks. They greased them with qui nine and lard. I asked a doctor in later years if he though[t] those remedies did any good. He said it did no harm to the patient and it did the women good [as] they thought they were doing something.

[18]

Garber School, 1890s. Floyd Jones is in back row, fourth from right end.

Children wore a bag of asaphetity [asafoetida] around their neck to keep from having contagious diseases. Mothers would chew the babys first food for them. These are just a few of the things they did which would be very much out of place today. They looked after their children them selves. They were not trusted to nurseries or baby sitters; they were always on the job.

The doctors recomended sassafras tea in the spring to thin the blood, and most people drink it through February and March. This was no problem as sassafras was a pest in the fields. The plows would turn it out [and] all we had to do was pick up the roots, chop them into small peaces and boil them in a tea kittle. We also made spice wood tea. Spice wood is a bush that grow[s] alond [along] the creeks. It has a very bushey top of small branches. The branches are very brittle and are easey broken in to short peaces to be boiled in the tea kittle for tea the same as the sas safras roots. It made a very flavorful tea.

We had no refrigeration and kept the milk and butter in the spring hous or hanging in the well. Most people dug roots for market such as ginsang, sinica [seneca,] golden seal or yellow root as we called it. The black smith made small narrow hoes for the pur pose. They would carry a sack tied around the shold ers to carry the roots in. They searched all through the woods for roots, washed and dried them and shipped them to st Louis to market.

I believe it was about 1880 a bunch of diggers found large flat rock about three inches thick and about two feet wide leaning aganst a tree and another rock the same size leaning aganst it. They moved the top rock for some reason and found this writing on the first rock. "This is Hell's half acre established by phil Sheridan in sixty two." The writing was very plain and neat cut into the stone with a sharp point. I looked at it many times and wonderd what it ment.4

After the Rail Road was built when I was about

[19]

fifteen years old I went by the spot and some one had broken the rock to peaces an dug up the ground all around it. We never did know who did it. I suppose they were looking for hidden treasure. I would give anything to have that rock today. We intend to go back and try to find some peaces of the rock with the writing on them. The spot is just a couple hundred yards from our old farm, a very rough rocky place about one fourth mile west of Roark Creek.

Bill Fronebarger put in a store and took over the Garber post office, moved it to his store at the forks of the creek. Later J K Ross put in a store on the RR at the Garber switch and became post master there.

We got our mail and did our trading at Branson. Uncle Rube Branson was the first mercha[n]t and pos master. The store was upon the hill just west of the grade school. There was a mill and cotton gin on the bank of the River. When I was quite small I went to this mill with father and saw ox teams pulling wag ons. The road came from the store down to the River between the Tom Berry and Bill Hawking [Hawkins] farms on up the River to the Ferry at the mouth of turkey creek.

Uncle Bill Hawking owned the ferry. He and the boys worked in the field near the ferry; when some one wanted to cross the river they would holler and he would leave his work in the field and ferry them over. He charged a fee. One day he lost a nickel going or coming from the ferry. He had all the boys to stop their work to help him look for the nickel. He said he dident care so much about the nickel [but] he would just like to know where he lost it.

Uncle Tom Berry had his black smith shop near the store. [It was] one of the real old village black smiths. All day every day you could hear his anvil ringing and see the sparks flying as he fitted horse shoes, welded wagon tires, built wagon wheels, sharpened plows, made gigs to gig fish. He was always buisy.

My first memory of going to Branson [was when] uncle Bill Hawkins was post master and kept the office in a lean to built on his house, which was locat ed west of the store known now as the Mrs. Stoffer place. The road from Branson to Springfield come down to Roark Creek at the old Zeb Stockstill place, up the creek to the forks, crossing the creek eight times, up the ridge between the two prongs of the creek to the old wilderness road at the Ben Stultz [Stults] place near Reeds spring, up the ridge to Highlandsville crossing Finley creek through Nixa, crossing James River and up the Campbell st road to springfield. The old wilderness road come into Missouri at Blue Ey, down the ridge to white river at Mayberrys ferry, up the ridge through ozark to the top of the dividing ridge between the white and osage Rivers, the top of the Ozark mountains. The road from Harrison, Ark to springfield come through Bear Creek springs up the ridge through Omaha, down the pinetop mountain, down over the bald glades through Kirbyville to the Hensley Ferry, up Bull Creek to wal nut shade, up Bear Creek through Reno to the old wilderness Road at spokane.

Kirbyville then was the largest business place in the west side of the county. Freight wagons were going both ways on this road all the time. Tracks cut into the solid rock by the wagon tires are still visible along the Bald. There were times when the River got too high to ferry and the wagons would pile up on each side and have to wait for several days before they could cross. When Bull and Bear Creeks were to high to cross they came up the River through the nar row up the Boston Road to the old wilderness [road] at the Reeds spring junction. Kirbyville had two large stores [and a] drug store, black smith shop, mill, cot ton gin. Our mail come from springfield to Chadwic by train [then] by hack to Forsyth; next day to Kirbyville where it was distributed for Branson and mincy. They got the mail by horse back.

All the livestock was driven over these road[s] to Ozark and springfield and shipped to St Louis to market. Even droves of turkeys were drove to mar ket. Following a drove of hogs was a slow tiresom job; they traveled so slow it took several days. Some hogs were hauled in wagons. In summer they traveled by night to keep the hogs from getting to hot. It was very easy to kill a fat hog in hot weather either driving or hauling them. Water along the road was a problem. We had a wagon along with feed and wattr. All the good[s] for southwest mo and north west ark were hauled over these roads.

It required four days to make the round trip from Branson to springfield. One wagon could carry fifteen hundred to two thousand pounds. Forty cents per hundred was the freight rate. There was always plen ty of company along the road and at the camp grounds at night. Wagons traveling both ways, you would meet as many wagons on the road then as you do cars today. There were a number of camp grounds along the road. Some of them had camp houses where you could cook and sleep for ten cents. We would

[20]

build a large camp fire and visit till bed time. They would trade horses and wagons. They had to be care ful about trading as there were horse traders, with no good horses that looked fine but were good for nothing but to cheat some one with. When they suc ceded in trading one of these horses to a freighter they would have some one else follow him and either trade for the horse or b[u]y him to trade to some other succer. We carried a grub box, frying pan and coffee pot and feed for the team. The nearer you got to springfield the mo[re] wagons on the road coming in from both sides.

When we got to springfield we stayed at a wagon yard where we could put the team in the barn and cook and sleep in the camp house for ten cents. You could get a large steak at the resterant for fifteen cents. We always tried to get into springfield early enough the second day to load up and be ready to start back home early the next morning. The road was rough up and down steep hills and bad mud holes. When we were heavy loaded we would dobel [double] team on the hard pulls, leaving one wagon and putting four horses on the other one, pulling it up the steep hill or bad mud hole then going back after the other one. We carried horse shoes, horse shoe nails and tools. If a horse lost a shoe he couldent go far without getting lame. We carried piecis of Boards to nail on the brake blocks as it dident take long to wear one out and a good break was a must. We had some trouble with wagon tires becoming loose in hot dry weather. If a tire should run off the wheel would very soon break to peaces, then we had to load it on a passing wagon and take it to the near est blacksmith shop and have it rebuilt. We carried soft pine wedges to drive under the tire and we drove them through water when we could or poured water on the wheels to tighten the tires [by making the wood wheel swell].

Mr Fronebarger trapped a bunch of wild hogs and hauled them to springfield to market. He drove into the wagon yard and a buyer came there and bought them in the wagon and told him to let them out of the wagon, and they would drive them into a pen. He [Fronebarger] told him, "these hogs will bite you." The man insisted and he kept telling him that these hogs will bite you. He finaly said, "they are my

[21]

hogs; turn them out [and] I will be resposible for them." He turned them out and they started fighting and scattered all over town and they dident get all of thim till the next day.

If some one wanted to make a trip to springfield they would ride a freight wagon. There were no labor orginations, no insurance, no sales tax, no income tax, no interest, no carrying charges, no gasoline, oil, or tires to buy, no cash for house rent, no preachers salleries to pay, no church buildings to build and maintaine. It was indeed a simple life; no one trying to keep up with the Joneses.

We had itch5 and head lice. It was no disgrac to get them but it was to keep them. I well remember us kids all having the itch at the same time. Mother would grease us with sulphur and lard then wash us with homade soap. It seemed we were being skinned alive. If that dident cure it she would boil green cedar twigs to make a tea that she washed us with. It was worse than the sulpher and lard, but she dident stop till the itch was gone. We would catch it at school, and we also got head lice at school. Then we were in for a lot of combing. She would get me between her [k]nees, scrap[e] my head with a fine tooth comb to get all the lice, then she would look for nits. When she found one she would pull it off the hair if the hair dident come first. She would work and cry till she got every nit. And I did more crying than she did.

I am not writing about this because I am proud of it, but because it is all true, and the picture would not be complete with out it. Neither do I want to make believe that I would like to go back to that kind of liv ing. My parents talked many times about selling the old farm and moving some where, where the children could get an education, but it was a hard job to sell. They talked about getting eight hundred dollars for the two hundred acres, the railroad came and they gave it up and stayed. The younger children got a fair education but the older ones got very little, as you can see by my writing.

It requires more education now; high school only prepares one for common labor now. If a person learnes all there is to learn now he would have so much knowledge that he couldent use it all. It is all cut up into different specialized studies. If one learns all about any one of them he is pretty well educated. Everything is highly specialized. The family doctor is a very important man in his community; if there is something too serious for him to handle he can guide you to the proper specialist, that is well trained in that special kind of work. This has caused many peo ple to enjoy longer and happier lives, [but] as they conquer one killer another shows up. They will never be able to keep us from dying with something because the living know they shall die. That is as cer tain as paying taxes so lets not condemn the doctors if some one happens to die. They are doing a wonder ful job, if every one was able to take advantage of their great skills. They spend half their lives prepar ing them selves to work the other half. They are inti tled to a lot of consideration.

I rember the first matches we got; they were large long sticks, had the picture of a mule on the box. We called them mule matches. When you would strike one it would fiz and smoke for a while, fill the house with sulphur fumes then blaze. Then we got a different kind of matches. They were smaller and would pop like a cap pistol. The kids would slip them out and pop them with a hammer.

Then mother got a cook stove. Father built another log house bout ten feet from the other one; he laid logs across from the top and put a roof over the space between them. Mother put the cook stove in the new house and used it for a kitchen and dining room. She also put a bed in the new room. This gave us more room. Mother then got a new sewing maching. It was a New Home [caps added] drop head. The agent brought it to the house and demonstrated it. Father wasent too much interested in buying it but mother was so he bought it, fifty five dollars on 9 years time.

We had a spring near the house that would always go dry in summer and we would have to carry water from a spring down on the creek bank about one fourth mile away and we either had to haul water to wash cose [clothes] or take them to the creek and wash them. Finely he had a well drilled right by the door. It was only twenty seven feet deep and stood half full all the time of cold clear water.

About 1895 I was big enough to help saw and we cut logs, hauled them to Bill Powels mill on fall creek and had lumber sawed to build a new box house. We built it one and one half stories high, made clap boards for the roof, went out on Dewey Bald, cut tim ber, dragged it with the team and made a large pile. Hauled lime stone rock, piled them on top and set fire to the log heap and burned lime to build the stone chimney and fireplace. We moved into it and wrecked the old log houses for fire wood.

To be continued.

[22]

This volume: Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues

Other Volumes | Keyword Search | White River Valley Quarterly Home | Local History Home

Copyright © White River Valley Historical Quarterly