Volume 4, Number 5 - Fall 1971

Oh Time and Change

By John Gerten

Our life of today differs from that of seventy-one years ago when a new century started.

How well I can remember that New Year’s night in our little Ozark Mountain home as we sat around the wood stove waiting of the new Century to come in.

My parents and their four children: As the old alarm clock on the corner shelf in the kitchen ticked off the last second of a dying year and a dying Century and the birth of a new. We celebrated the event by drinking a pot of coffee and eating a pumpkin pie. Today there are only two of us left, my sister Margaret and myself.

The turn of the Century was the beginning of many changes. Improvements were being made that should help humanity. We in the hills began to hear of the horseless carriage, wireless telegraphy, smokeless powder, hammerless guns, electric lights, and even talking machines.

These new inventions were but the forerunner, the mechanical age had arrived. Yet in our quiet Ozark hills it would be some time before one would notice much change. Flying machines would soon be invented, but so far the skies were strictly for the birds.

Our nearest railroad was still some thirty-five miles away, at Chadwick or "Chad" as the freighters called it. Freight was being hauled via the big road from Springfield, fifty miles away to the north of us to across the border into "Arkansaw". The word Arkansas was never used in the hills in those days.

The Big Road was the lifeline of the hills that supplied the General stores with such articles as were needed in our every day life. The road was rough due to the fact that very little work was done to improve it. This work was called working out one’s poll tax. Every man over twenty-one or voting age was required to work four days on the road each year or two days with a team. This work was not much more than a "lick and a promise", but was the best that could be done considering the time and number of men.

The life that people lived in the hills at that time might be considered dull today as far as entertainment went. There was the Sunday gathering at the Meeting house and now and then a box or pie supper, and square dances; but for the most part it was more work than play or entertainment.

The Civil War ended some thirty-five years before. There had been some shooting going on in the hills for some time after, but quiet had now settled on the land and the sounds one heard most were the tinkling of the cow bells, the song of many birds, and the gobbling of wild turkeys.

One spring evening the first year we lived in the hills, one of our family heard a cry that seemed to come from up on the nearest hillside. Calling for the rest of us to come out and hearing the cry or scream again, we all stood listening not knowing what to make of it. The cry was repeated several times more and seemed to be moving towards the top of the hill.

Now we did not hear it any more so going back into the house we resolved to mention it to our neighbors the Russell family. The next day being Sunday "Uncle Buck" Russell dropped by, as usual, to chat with my father and was told about the strange cry we had heard. Uncle Buck listened to our description of the cry then said "What you folks heard last night was a "painter".

Whether this was the answer to the mystery we never knew. Years later the question was once argued in a hunting magazine about the cry of the panther. Some woodsmen claimed a panther screamed and some claimed that he did not. Whoever was in the right it is certain that if what we heard that night was a "painter" he had done some screaming.

Our work went on, to clear up a home in the wilderness with only small incidents to break the monotony; such as beating out a woods fire to save our rail fence or driving out a bunch of mules who had jumped the fence into our cornfield; or the time we were eating our breakfast and our young cat came proudly walking in and deposited a live tarantula in the midst of the kitchen floor.

In a moment all hell had broken loose and high spots on which to climb were at a premium. My father picking up a stick of stove wood dispatched the unwelcome gift

[1]

from our kitten who seemed to think she should be praised for her catch. No praise or thanks were offered to her by any of the family who now coming down from on high finished their breakfast.

Looking back, I wonder if life in the hills in those days with all its hardships and lack of modern conveniences did not have many things lacking today. There seemed a different family life and a different spirit towards one’s neighbors that would be hard for many to understand when born in later years.

The old coal oil lamp had not outlived its usefulness yet and still cast its mellow glow on the faces of the family circle gathered around it on the long winter evenings.

I will try to describe our own family life as an example of how we passed these evenings after the day’s work was done and the table had been cleared after the evening meal and it was time to relax.

Sometimes it would be reading with each member of the family absorbed in his or her own particular story. There were such magazines as Peoples Home Journal, Ladies Home Companion, Farm and Fireside, and others such as Good Stories, Comfort and Vickerys Fireside Visitor. We had books such as Woods Natural History, Beauties and Wonders of Land and Sea. My favorite book was Robinson Crusoe which I could read over and over and never tire of it. There was something about poor Robinson’s simple life and problems that faced him from day to day that he must overcome that were somehow similar to our own life in the hills.

[2]

There were also paper back novels such as Corsican Brothers by Dumas, Around the World in Eighty Days, and A Trip to the Moon by Jules Verne. Could he have but looked into the future and see what is happening today!

There were also late novels such as Lena Rivers and Tempest and Sunshine which were quite popular at the time.

We had subscribed to the St. Louis Republic which was the only way of knowing what was going on in the outside world. Besides the news they ran such continued stories as The Moonstone, The Last of the Mohicans, and the Pathfinder. These tales were so real and exciting to us children that we could hardly wait for the next copy to arrive.

Not all of our evenings were spent in reading. There were evenings when we would all sit around the stove and sing. Our parents had taught us to sing German songs and many a long winter evening all six of us would sing the songs our parents had sung in the Old Country, some no doubt had been sung by their parents and grandparents.

Our singing was our only music as we had no musical instruments of any kind and there were few people that did. Some had a fiddle.

In the summertime our singing was carried on out under the trees that had been left for shade around the house. Here in the evenings we would sit on some benches our father had made. The fireflies were flashing their lights. The katydids and the tree frogs also held their evening concert.

Some times during the winter evening our parents would tell stories and we would all listen. These were mostly stories from the old country. Our father would tell stories about Baron Munchhausen who could have joined the Liars Club were he alive today. Pa would also tell ghost stories that would make one's hair stand on end and going out in the dark I would see a ghost in every bush.

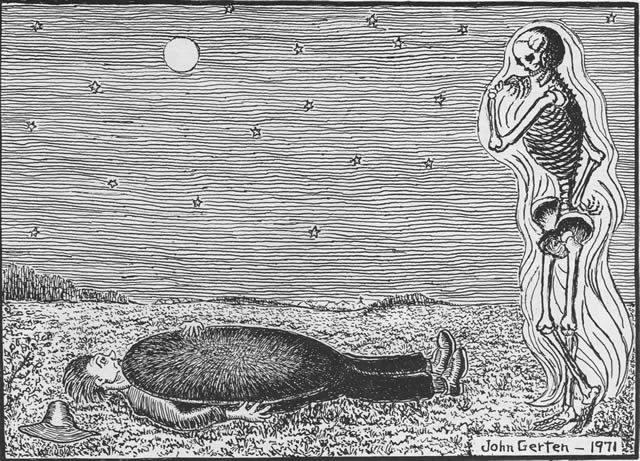

Not all of my father's ghost stories were blood burdling some even had a bit of humor in them as the one about the farm hand who had gone to the neighboring farm to help winnow grain. The day had been warm and the food and drink plentiful. The farm hand had eaten heartily of the farmer's food and imbibed his share of the drink. The latter, no doubt, to wash the chaff and dust out of his throat.

It was quite late when all was finished so taking one more departing drink he took his large winnowing pan and set out on his journey home. It was a clear moonlight night and his way lay through a lonely meadow. He had traveled nearly the length of it when becoming drowsy he decided to lie down and rest a bit. Pulling the large pan over his body so that only his legs protruded he promptly fell asleep.

How long he lay there he did not know. He awoke suddenly with the feeling that something or someone was watching him. Peering over the edge of his pan he beheld a ghost standing near his feet looking down at him. For sometime neither spoke. The farm hand could not speak for terror and the ghost could not for astonishment.

At last the ghost found his voice and in a hollow tone spoke these words, "Three times have I seen this land in forest and three times in meadow, but never before have I seen a winnowing pan with legs."

The ghost then walked slowly away in a dignified manner as ghosts do. Had he looked back he would have beheld the winnowing pan with legs traveling in the opposite direction without dignity, but with great speed.

Ma would also sometimes relate amusing incidents that had happened - for instance, the story about the puppets.

It was during the annual Kermis or fair in the small village where she was born and which all the country folks round about did not fail to attend. The puppen or puppets had been cleverly fashioned from vegetables. With the proper manipulation of a number of strings, the puppets seemed to be human.

It was while the woman who manipulated these strings was busy out in front taking in the pfenings (money) from the country folks for admission to the exciting shows that one of the village hogs nosing about in search of something to eat had "snuk" in unbeknown to anyone much as a small boy might have done. Spying the puppets the hog sampled one, finding it to his taste, promptly ate the rest.

Now with her spiel out front finished and her pockets filled with coins the woman returned backstage to start the show. One glance was enough to tell the story. With a yell of fury and swift aimed kick she chased the hog outside, but it was too late. The beast now outside was also on the outside of all her puppets and her audience was waiting.

[3]

Stepping up on the stage she announced that their pig had eaten all her puppets and there would be no show and they would not get their money back.

Ma would sometimes speak of France where she had spent a couple of years as a young woman. She had first gone to Nancy and later to Paris. There she served as a governess and taught the young son German. The grandfather of the small boy was still living and was the only survivor of a large family. They had all been Nobles or Aristocrats and all had been beheaded during the Reign of Terror in 1793. He, as a small child, had been carried away by friends who were fortunate enough to make their escape.

Ma would speak of the Tuileries and the Louvre, of the Champ Elysees, Foubourgh, St. Germain, and of San Sulpice.

She recalled having seen Napolean III in a coach drawn by six white horses as he and the Empress Eugenie had passed through the streets of Paris. The Empress was dressed in white and wore a large white hat with an ostrich plume. What Napolean wore she did not say.

Ma still remembered some French songs. She would now and then sing one of them as she went about her work. There was a song about the Moon that she would sing "Au Clair de la lu-ne Mon a-mi Pier -rot. Pre te moi to plu-me pour-l crire un mot." Margaret and I would sometimes try and sing it too. The tune was a simple one and easy to follow, but the words we garbled so that satan himself would not have recognized them, much less a Frenchman.

[4]

And so time marched on. There were not many changes in the hills as yet. We heard rumors that a telephone line was being built into the hills and had reached as far as Kissee Mills and Forsyth. It happened we had some freight coming by R.R. to Chadwick, the end of the line and from there on must be brought by wagon.

Mr. Muller told us that a freighter had left Cedar Creek that morning for Chadwick and if I would walk to Polk McHaffie’s farm which was just across Beaver Creek from Kissee Mills, and who had a telephone, I could get a message through to the depot at Chadwick where the freighter was going before he got there and he could pick up our freight. So starting out I made the eight mile walk to the McHaffie place and paid my twenty-five cents to have the message sent, which I think did not go through direct but was relayed by way of Forsyth. But somehow the message did not reach the freighter and he came back without our freight.

I did not mind as much that I had walked sixteen miles in vain as that I was out a hard-earned twenty-five cents.

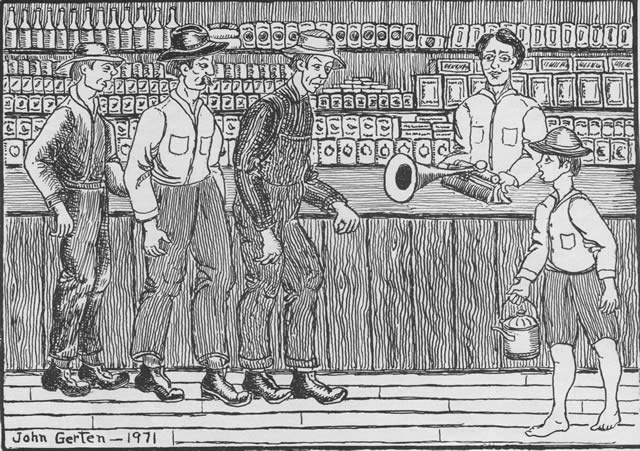

Now there were more new inventions finding their way into the hills. Coming into the general store one day I joined a group that stood staring at a marvelous machine that had just arrived. It was a talking machine which actually talked and even sang. After it had been wound up by the merchant it struck up a tune called "Strike Out McCracken." It was a comical song about a Scotchman who had somehow fallen into the sea. The shock to McCracken on striking the cold water could not have been worse than it was to me when this strange contraption with its human voice started up. It was "uncanny" as the Scotch-man himself might have said.

All this was in the long ago and no doubt young people today will smile to think how simple we must have been in those days, but at the rate the World is changing who knows what the next seventy-one years will bring?... I will not be around to see.

[5]

This volume: Next Article | Table of Contents | Other Issues

Other Volumes | Keyword Search | White River Valley Quarterly Home | Local History Home

Copyright © White River Valley Historical Quarterly